The Presidio Past and Present

We hailed a car marked "Exposition" and were soon climbing the hills to the west. Between the houses, we had fleeting glances of the bay with its freight of vessels. Here waved the tri-color of France, while next to it the black, white and red flag of Germany was flung to the breeze, and within a stone's throw, Johnny Bull had cast out his insignia. At a little distance the ships of Austria and Russia rested side by side, and between the vessels the bustling little ferry-boats were churning up the blue water.

"It is difficult to picture this bay as it was in early Spanish days," I said, "destitute of boats and so full of otter that when the Russians and Alaskan Aleuts began plundering these waters, they had only to lean from the canoes and kill hundreds with their oars."

"But what right had the Russian here? Why didn't the Spaniards stop them? Otter must have brought a good price in those days." There was a ring of indignation in his voice, that told his interest had been aroused.

"San Francisco was helpless. There was not a boat on the bay, except the rude tule canoes of the Indians - 'boats of straw' - Vancouver called them, and these were no match for the swift darting bidarkas of the Alaskan natives."

"And Luis Argüello in command!"

"I saw my idol falling, and hastened to assure him that the Comandante had built a boat a short time before, but the result was so disastrous that he never tried it again. The Presidio was in great need of repair and the government at Mexico had paid no heed to the constant requests for assistance, so Comandante Argüello had determined to take matters into his own hands. The peninsula was destitute of large timber, but ten miles across the bay were abundant forests, if he could but reach them. He, therefore, secured the services of an English carpenter to construct a boat, while his men traveled two hundred miles by land, down the peninsula to San Jose, along the contra costa, across the straits of Carquinez and touching at the present location of Petaluma and San Rafael, finally arrived at the spot selected. In the meantime the soldiers were taught to sail the craft, and the first ferryboat, at length started across the bay. But a squall was encountered, the land-loving men lost their heads, and it was only through Argüello's presence of mind that the boat finally reached its destination. For the return trip, the services of an Indian chief were secured, a native who had been seen so often on the bay in his raft of rushes, that the Spaniards called him 'El Marino,' the Sailor, and this name, corrupted into Marin, still clings to the land where he lived. Many trips were made in this ferry, but the comandante's subordinates were less successful than he, for one, being swept out to sea, drifted about for a day or two until a more favorable wind and tide brought him back to San Francisco. The Spaniards called the land where the trees were felled 'Corte Madera,' the place of hewn-wood, and a little town on the site still bears the name."

"But what became of the boat? You said -"

"Governor Sola was furious that any one should dare to build a boat without his orders. He called it 'insubordination.' How did he know what was the real purpose of the craft? Might it not have been built to aid the Russians in securing otter or to help the 'Boston Nation' in their nefarious smuggling?"

My companion straightened with interest, "The Boston Nation?"

"Yes, even in those days the Yankee skippers, who occasionally did a little secret trading with the padres, told such marvelous stories of Boston that the Spaniards thought it must be a nation instead of a little town. In fact, the United States does not seem to have been considered of much importance by Spain, for when the American ship 'Columbia' was expected to touch on this coast it was referred to as 'General Washington's vessel.'"

"Go on with your boat story," a smile played about the corners of his mouth. "What became of the craft?"

"The Governor ordered it sent to Monterey and commanded Argüello to appear before him. The Comandante was surprised to have his work thus suddenly interrupted but hastened to obey orders. On the way his horse stumbled and fell, injuring his rider's leg so seriously that when Argüello reached Monterey, he was hardly able to stand. Without stopping to have his injury dressed, he limped into the Governor's presence, supporting himself on his sword.

"'How dared you build a launch and repair your Presidio without my permission?' exclaimed the exasperated Governor.

"'Because I and my soldiers were living in hovels, and we were capable of bettering our condition,' was the reply.

"Governor Sola, not noted for his genial temper, raised his cane with the evident intention of using it, when he noticed that the young Comandante had drawn himself erect and was handling the hilt of his naked sword.

"'Why did you do that?' the Governor demanded.

"'Because I was tired of my former position, and also because I do not intend to be beaten without resistance,' Argüello answered.

"For a moment the Governor was taken back, then he held out his hand. 'This is the bearing of a soldier and worthy of a man of honor,' he said. 'Blows are only for cowards who deserve them.'

"Argüello took the outstretched hand and from this time he and the Governor were close friends. But the boat proved so useful at Monterey, that it was never returned."

The Jeweled Tower of the Exposition came into view. "So it is to be the three months' old World's Fair, after all, instead of the home of the first Mexican Governor of California?"

But I did not rise. "The Presidio is just beyond," I explained. Then seeing him glancing admiringly at the green domes: "Perhaps you would rather—"

"No," he answered me, "I'm an antiquary and I want to see the old adobe house."

Leaving the car at the Presidio entrance, we passed down the shaded driveway and along the winding path that led to the old parade ground. "This military reservation covers about the same ground as the old Spanish Presidio," I explained. "At that time, however, it was a sweep of tawny sand-dunes, for the Spaniards had neither the ability nor the money to beautify the place. After it came into possession of the Americans, lupins were scattered broadcast as a first means of cultivation and for a time the undulating hills were veiled in blue. Later, groves of pine and eucalyptus trees together with grass and flowers were planted, until now it may be regarded as one of the parks of San Francisco. This was the original plaza of the old Spanish Presidio," I continued, as we emerged onto the quadrangle, "and it was then lined with houses as it is today, only at that time they were crude adobe structures. Surrounding these was a wall fourteen feet high, made of huge upright and horizontal saplings plastered with mud, and as a further means of protection, a wide ditch was dug on the outside. Here Luis Argüello was Comandante for twenty-three years."

Our eyes wandered over the substantial structures with their well-trimmed gardens and rested on a low rambling building opposite, protected from the gaze of the curious by an old palm and guarded by a quaint Spanish cannon. The building's simple outlines, even at a distance, bespoke it as of a different generation from its more aggressive neighbors, even though its red-tiled roof had been replaced by sombre brown shingles, and its crumbling walls replastered. We crossed over the parade ground, and peering within, found that the building had been converted into an officers' club house.

"Did you see the bronze tablet on the front?" I demanded.

"Yes," he admitted rather sheepishly, turning to examine the deep window embrasure that showed the width of the walls.

"There's an atmosphere of romance about the old place..."

"And well there may be," I broke in, "for it was here that Rafaela Sal came as a bride, and that Rezánov met Luis Argüello's beautiful sister, Concepcion, and a love story began which may well take place with that of Miles Standish and Priscilla."

Rezánov," he repeated, searching his memory. "I recall that there was a romance connected with

his visit to San

Francisco but the details have escaped me. Please sit

down on this bench and tell me the story just as if I had never heard it before."

Rezánov," he repeated, searching his memory. "I recall that there was a romance connected with

his visit to San

Francisco but the details have escaped me. Please sit

down on this bench and tell me the story just as if I had never heard it before."

"More than a century ago there dwelt in this old adobe house a beautiful maiden," I began. "Her father was Comandante of the Presidio, 'el Santo,' the people termed him, because of his goodness. Concepcion, or Concha, as she was affectionately called by her parents, was only fifteen years old when our story begins—a tall, slender girl with masses of fine black hair and the fair Castilian skin, inherited from her mother. So lovely was she that many a caballero had already sung at her grating, but she would listen to none of them. Her lover would come from over the sea, she declared, someone who could tell her about the wide outside world.

"'Then you will die unmarried,' said her

mother, kissing the soft cheek, 'for travelers seldom come as far as

San

Francisco.'

"'A ship! a ship!' sounded a cry from the plaza. A vessel had been sighted off Cantil Blanco, the first foreign ship seen since Vancouver's visit fourteen years before.

"'It is the Russian expedition which Spain has ordered us to treat courteously,' exclaimed Don Luis, bursting into the house, his face aglow with excitement. 'Since father is in Monterey and I am acting Comandante, I must receive these strangers,' he continued as he threw his serape over his shoulders, his eyes flashing with his first taste of command.

"'Be careful,' cautioned his mother, 'we have had no word from Europe for nine months and the last packet boat from Mexico brought a rumor of war with Russia.'

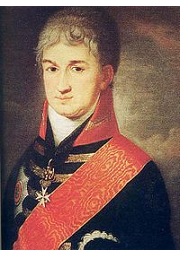

"But the foreign vessel had come only with friendly intentions. The Russian Chamberlain Rezánov, in charge of the Czar's northwestern possessions, had found a starving colony at Sitka and had brought a cargo of goods to the more productive southland with the hope of exchanging it for foodstuffs. To be sure, he knew the Spanish law strictly forbidding trade with foreign vessels, but it seemed the only means of saving his famishing people and he trusted much to his skill in diplomacy.

"A few hours later, Concha, on the qui vive with excitement, saw her brother approaching with a little company of men, among whom was a tall well-built Russian officer, whose keen eyes seemed to take in every detail of the little settlement.

"Don Luis conducted his guests to the old adobe building, draped in pink Castilian roses, and into the cool sala, which, although provided with slippery horse-hair chairs and plain whitewashed walls ornamented with pictures of the Virgin and saints, was a pleasing contrast to the ship's cabin. Here he presented his guests to his mother, a woman whose face still reflected much of the beauty of her youth in spite of her cares which had come in the rearing of her thirteen children. Beside her stood Concepcion. Her long drooping lashes swept her cheeks, but when she raised her eyes in greeting Rezánov saw that they were dark and joyous. He was a widower of many years, a man of forty-two, who had given little thought to women during his wandering life, but now he found himself keenly alive to the charms of this radiant girl. Simple and artless in her manners, yet possessing the early maturity of her race, she set her guests at ease and entertained them with stories of life on the great ranchos, while her mother was busy with household duties.

"It was ten days before Don José Argüello returned from Monterey and in the meantime no business could be transacted. During these days Rezánov saw much of Concepcion, for there was dancing every afternoon at the home of the Comandante and frequent picnics into the neighboring woods. It was not long before the Russian learned that Concepcion was not only La Favorita of the Presidio, but also of all California, for although born at San Francisco, she had spent much time in her childhood at Santa Barbara, where her father had been Comandante. With a chain of missions and ranchos extending from San Diego to San Francisco, there was much interchange of hospitality, and Concha was a favorite guest at all fiestas. So the dark eyed Spanish girl had danced her way into the heart of many a youth as she was now doing into that of this powerful Russian.

"Often he would stand in the shadow of the deep window casement and watch her lithe young figure bend in the graceful borego, occasionally catching a glance from beneath the sweeping lashes that would send his blood surging through his veins and make him almost forget the purpose of his voyage. Sometimes he would draw her aside to talk of his hope that the Spaniards would furnish him bread-stuffs for his starving colony and he marveled at her keen insight into the affairs of state, while his heart beat the quicker for her warm sympathy. Often their talk would wander to other things and as she occasionally flashed a smile in his direction, showing a row of pearly teeth, his blood tingled and he thought that the flush on her cheek was not unlike the pink Castilian rose that was nightly tucked in the soft coils of her shadowy hair. At times he imagined her clad in rich satin, with a rope of pearls about her delicate throat, and as he drew the picture he saw her as a star among the ladies of the Russian court.

"When Don José Argüello returned, Rezánov asked him for the hand of his daughter in marriage, but the Comandante indignantly refused. Although liking the distinguished Russian for himself, he would not listen to such a proposal. Give his daughter to a foreigner and a heretic! Never! It was not to be thought of for an instant. Concha must be sent away. She must not see this Russian again! He would have her taken to the home of his brother, who lived near the Mission, until the foreign ship was out of the bay. While the father talked, the mother hurried to the padres to beg the good priests to forbid such a union.

"But Concha was no longer the docile girl of a month ago. She was a woman and her heart was in the keeping of this sturdy Russian. She would have him or none, and nothing the padres or her parents could say would change her. Don José had never crossed his daughter before, and now as she flung her arms about his neck and begged for her happiness he weakened. After all, this Russian was a splendid fellow, and perhaps it might be an advantage to Spain, rather than a detriment to have an ally at Petrograd. In the end the pleading of Concha and the arguments of Rezánov won. Comandante Argüello yielded and the betrothal was solemnized, but there were many obstacles before the marriage could be consummated. The permission of the Czar of Russia and the King of Spain must be obtained, and this would take time, as well as involve a long and dangerous trip. But nothing could daunt the spirits of the lovers. Concepcion's brother, Luis, had already waited six years for permission to marry Rafaela Sal and if Rezánov traveled with haste he could return in two. He must go first to Petrograd to ask the consent of the Czar and then to the Court of Madrid to promote more friendly relations between the two countries, finally returning to claim his bride, by way of Mexico. But before he could start on his journey, his starving Alaskan colony must be provided for, and after considerable discussion, arrangements were made for an interchange of commodities, and the hold of the Russian ship, 'Juno' was packed with foodstuffs for the Sitkans, while the ladies at the Presidio were resplendent in soft Russian fabrics and the padres were rejoicing in new cooking utensils for their large Indian family.

"At length the 'Juno' weighed anchor and the white sails filled with the afternoon breeze. As the Russians came opposite Cantil Blanco, the fort which had scowled so menacingly upon them on their entrance forty-four days before, now smiled with friendly faces. There was much waving of hats and many shouts of farewell from the little group on the shore, but Rezánov saw only the figure of a tall graceful girl with the soft folds of a mantilla billowing about her head and shoulders and heard only the murmur of love from the rosy lips. 'Two years,' he whispered back to her, as the ship passed out through the Gulf of the Farallones and became but a speck on the sunset sky.

"The two years passed and still there was no sign of the returning vessel. Luis Argüello had been married to the lovely Rafaela and a little son had come to bless their household, and yet Concepcion looked out over the ocean watching for the white sail of a foreign ship. The sweet grey eyes of Luis' young wife were closed in death and Concha's heart and hands went out in sympathetic love and deeds to the stricken family, all the while trying to still in her own breast the fear that a like fate had overtaken her loved one. The verdant hills were again streaked with golden poppies and once more turned to tawny brown and still no ship nor word came from over the sea.

"It was eight or ten years before even a rumor of the fate of her lover reached Concepcion, and not until she met the Englishman, Sir George Simpson, twenty-five years after Rezánov sailed out of San Francisco bay, did she learn the details of his death. It was almost winter when, leaving Alaska, he crossed the ocean and began his perilous trip through Siberia. Frequently drenched to the skin and undergoing terrible privations, he traveled for thousands of miles on horseback, now lying at some wayside inn burning with fever and again pushing on until he dropped prostrate at the next village. A fall from his horse added to his already serious condition, which resulted in his death in the little village of Krasnoiark, and he lies now buried beneath the snows of Siberia.

"Although many sought her hand in marriage, Concepcion remained faithful to her Russian lover. There being no convent for women in the country at that time, she donned the grey habit of the 'Third Order of St. Francis in the world,' devoting her life to the care of the sick and the teaching of the poor. Later when a Dominican convent was established," I added, rising, "she became not only its first nun, but also its Mother Superior."

"A romance that may well take a place with such world-famed love stories as those of Abèlard and Hèloïse; and Alexandre and Thäis. I should like to make a pilgrimage to her grave," he added as we left the old adobe house.

"You can," I replied. "It's tucked away in a corner of the Benicia Cemetery, marked by a marble slab carved with her name and a simple cross."

We entered a grove of eucalyptus trees, which now and again divided, giving marvelous views of the bay and the Marin shore.

But my companion's mind still dwelt on the story he had heard. "So Concepcion suffered in the uncertainty of hope and despair for ten years," he said, "but ten months of it brought me to the limit of endurance. Do you think if Rezánov had returned and Concepcion had married him and gone to Petrograd she would have been happy?"

"Of course she would."

"Still Petrograd is a cold, dreary place compared to California."

"But what difference would that make? A woman would give up everything and count it no sacrifice for the man she loved."

"And you said only yesterday—"

"Oh, but that was different," I assured him, my cheeks burning under his gaze. "Rezánov loved California. He thought it so wonderful that he wanted it for a Russian province, and he would have brought Concepcion back to visit—"

"Boston is nearer than Petrograd and not so cold. Don't you think you could teach me to love California, too?"

"Perhaps," I acknowledged. Then anxious to turn the conversation, I asked: "Would you like to see the location of the old Spanish fort?" He nodded and we took the road leading to the present Fort Point. "I can't show you the exact location," I confessed, "because the United States cut down the bold promontory, Cantil Blanco, in order to place the present fortification close to the water's edge, but if you will use your imagination and picture a white cliff towering a hundred feet above the water at the point where Fort Winfield Scott now stands, you will see the entrance to the bay as it was in Spanish days. Here was located the old fort, called Castilla San Joaquin, which guarded the harbor for many years. Made of adobe in the shape of a horseshoe, so perishable that the walls crumbled every time a shot was fired, still it answered its purpose, as it was never needed for anything but friendly salutes, and even these were at times, perforce, omitted. The Russian, Kotzebue, states that when he entered the harbor he was impressed by the old fort and the soldiers drawn up in military array, but wondered that no return was made to his salute. A little later, however, the omission of the courtesy was explained when a Spanish officer boarded the vessel and asked to borrow sufficient powder for this purpose. Moreover, Robinson tells us that frequently during the afternoon's siesta a foreign ship would pass the fort, drop anchor in Yerba Buena Cove, and spend several days in the bay before the Presidio officers would know of its presence. But this was after the time of Luis Argüello."

One by one the palaces of light in the Exposition grounds below us burst into radiance. The Horticultural dome turned to a wonderful iridescent bubble and the Tower of Jewels caught and reflected the light that played upon it. Wide bands of color streaked the sombre sky, transforming the clouds to shades of violet, yellow and rose. "The rainbow colors of promise," he said gently as he drew closer. "I shall take them as a message of hope that I shall win the love of the woman who is dearer to me than all else in life!"