|

The

History of London - George II

|

59. UNDER

GEORGE THE SECOND.

PART V.

It was estimated, some years later than the period we

are considering, that there were then in London 3,000 receivers of

stolen goods; that is to say, people who{219}

bought without question whatever was brought to them for sale: that the

value of the goods stolen every year from the ships lying in the

river—there were then no great Docks and the lading and

unlading were carried on by lighters and barges—amounted to

half a million sterling every year: that the value of the property

annually stolen in and about London

amounted to 700,000l.:

and that goods worth half a million at least were annually stolen from

His Majesty's stores, dockyards, ships of war, &c. The moral

principle, a writer states plainly, 'is totally destroyed among a vast

body of the lower ranks of the people.' To meet this deplorable

condition of things there were forty-eight different offences

punishable by death: among them was shoplifting above five shillings:

stealing linen from a bleaching ground: cutting hop bines and sending

threatening letters. There were nineteen kinds of offences for which

transportation, imprisonment, whipping, or pillory were provided: there

were twenty-one kinds of offences punishable by whipping, pillory, fine

and imprisonment. Among the last were 'combinations and conspiracies

for raising the price of wages.' The classification seems to have been

done at haphazard: for instance, to embezzle naval stores would seem as

bad as to steal a master's goods: but the latter offence was capital

and the former not. Again, it is surely a most abominable crime to set

fire to a house, yet this is classed among the lighter offences. It was

therefore a time when there was a large and constantly increasing

criminal class: and, as a natural cause or a natural consequence,

whichever we please, there was a very large class of people as

ignorant, as rude, and as dangerous as could well be imagined. I do not

think there was ever a time, not even in the most remote ages, when

London contained savages more brutal and more ignorant than could be

found in certain{220} districts

outside the City of the Second George. But these poor wretches had one

great virtue—they were brave: they manned our ships for us

and gave Britannia the command of the sea: they were knocked down,

driven and dragged aboard the ships by the press-gang. Once there they

fell into rank and order, carried a valiant pike, manned the guns with

zeal, joined the boarding party with alacrity and carried their

cutlasses into the forlorn hope with faces that showed no fear. They

were so strong, so stubborn, and so brave, that one sighs to think of

the lash that kept them in discipline and order. There is one more side

of London that must not be forgotten. It was a great and prosperous

city: we can never dwell too strongly on the prosperity of the city:

but there were shipwrecks many and disastrous. And the fate of the man

who could not pay his debts was well known to all and could be

witnessed every day, as an example and a warning. For he went to prison

and in prison he stopped. 'Pay what you owe,' they said to the debtor,

'or else stay where you are.' The debtor could not pay: in prison the

debtor had no means of making any money: therefore he stayed where he

was until he died. For the accommodation of these unhappy persons there

were the King's Bench and the Marshalsea, both in Southwark: there were

the two Compters, both in the City: and there was the Fleet Prison.

The life in these prisons can be found described in

many novels. It was a squalid and miserable life among ruined gamblers,

spendthrifts, profligates, broken down merchants, bankrupt tradesmen,

and helpless women of all classes. Unless one had allowances from

friends, starvation might be the end. In one at least the common hall

had shelves ranged round the walls for the reception of beds:

everything was carried on in the same room,{221}

living, sleeping, eating, cooking. And into such a place as this the

unhappy debtor was thrust, there to remain till death released him.

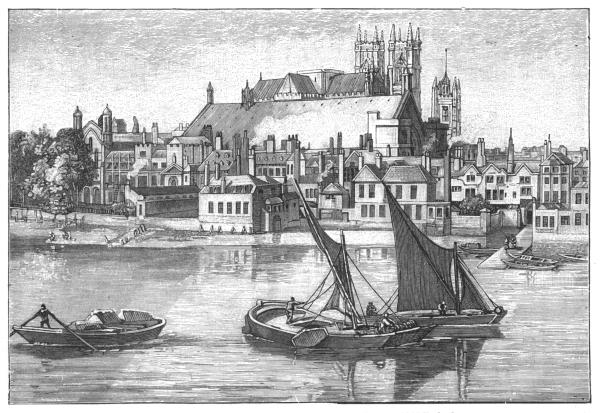

THE

OLD HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT AND WESTMINSTER ABBEY, 1803.

THE

OLD HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT AND WESTMINSTER ABBEY, 1803. {222}This was the

London of a hundred and fifty years ago. No longer picturesque as in

the old days, but solidly constructed, handsome, and substantial. The

merchants still lived in the city but the nobles had all gone. The

Companies possessed the greater part of the City and still ruled though

they no longer dictated the wages, hours, and prices. Within the walls

there reigned comparative order: outside there was no government at

all. The river below the Bridge was crowded with ships moored two and

four together side by side with an open way in the middle. Thousands of

barges and lighters were engaged upon the cargoes: every day the church

bells rang for a large and orderly congregation: every day arose in

every street such an uproar as we cannot even imagine: yet there were

quiet spots in the City with shady gardens where one could sit at

peace: wealth grew fast: but with it there grew up the mob with the

fear of anarchy and license, a taste of which was afforded by the

Gordon Riots. Yet it would be eighty years before the city should

understand the necessity for a police.

London Sights to See

St. Paul's Cathedral

Buckingham

Palace

Elfin

Oak of Kensington Gardens

Shakespeare's

Globe Theatre

Harrod's

Department Store

Hyde

Park

Kensington

Palace and Gardens

Kew

Palace and Gardens

Madame

Tussauds Wax Museum and London Planetarium

Piccadilly

Circus

Royal

Observatory, Greenwich

The

West End

Trafalgar

Square

Westminster

Abbey

Whitehall

Sitemap

Home

Based Travel Business

Free

Advertising