HOW TO GET ON IN THE WORLD; or, A LADDER TO PRACTICAL SUCCESS.

by MAJOR A. R. CALHOUN.

CHAPTER XIX

SINGLENESS OF PURPOSE.

We have all heard of the "Jack of all trades, and master of none." Such men never win, though they may excite the admiration of the curious by their impractical versatility.

In early times, even in the early settlement of our own country, it

was necessary for not only men, but women also, to be many-sided in

their capacity for work; but the world's swift advance has made this

unnecessary. A farmer can now buy shoes cheaper than he could make

them at home, and the farmer's wife has no longer to learn the art of

spinning and weaving.

In early times, even in the early settlement of our own country, it

was necessary for not only men, but women also, to be many-sided in

their capacity for work; but the world's swift advance has made this

unnecessary. A farmer can now buy shoes cheaper than he could make

them at home, and the farmer's wife has no longer to learn the art of

spinning and weaving.

A French philosopher in speaking of this subject says: "It is well to know something about everything, and everything about something." That is general information is always useful, but special information is essential to special success.

The field of learning is too vast to be carefully gone over in one lifetime, and the business world is too extensive to permit any man to become acquainted with all its topography. A man may do a number of things fairly well, but he can do only one thing very well.

Often versatility instead of being a blessing is an injury. A few men like Michael Angelo in art, Benjamin Franklin in science and letters, and Peter Cooper in various departments of manufacture have succeeded in everything they undertook, but to hold these up as examples to be followed would be to make a rule of an exception.

Singleness of purpose is one of the prime requisites of success. Fortune is jealous, and refuses to be approached from all sides by the same suitor.

We have known men of marked ability, but want of purpose, who studied for the ministry and failed; who then studied law—and failed. After this they tried medicine and journalism, only to fail in each; whereas, had they stuck resolutely to one thing success would not have been uncertain.

A young man may not be able at the very start to hit upon the vocation for which he is best adapted, but should he find it, he will see that his ability to avail himself of its advantages will depend largely on the energy and singleness of purpose displayed in the work for which he had no liking.

There is a famous speech recorded of an old Norseman, thoroughly

characteristic of the Teuton. "I believe neither in idols nor

demons," said he; "I put my sole trust in my own strength of body and

soul." The ancient crest of a pickaxe with the motto of "Either I

will find a way or make one," was an expression of the same sturdy

independence which to this day distinguishes the descendants of the

Northmen. Indeed, nothing could be more characteristic of the

Scandinavian mythology, than that it had a god with a hammer.

There is a famous speech recorded of an old Norseman, thoroughly

characteristic of the Teuton. "I believe neither in idols nor

demons," said he; "I put my sole trust in my own strength of body and

soul." The ancient crest of a pickaxe with the motto of "Either I

will find a way or make one," was an expression of the same sturdy

independence which to this day distinguishes the descendants of the

Northmen. Indeed, nothing could be more characteristic of the

Scandinavian mythology, than that it had a god with a hammer.

A man's character is seen in small matters; and from even so slight a test as the mode in which a man wields a hammer, his energy may in some measure be inferred. Thus an eminent Frenchman hit off in a single phrase the characteristic quality of the inhabitants of a particular district, in which a friend of his proposed to settle and buy land. "Beware," said he, "of making a purchase there; I know the men of that Department; the pupils who come from it to our veterinary school at Paris do not strike hard upon the anvil; they want energy; and you will not get a satisfactory return on any capital you may invest there."

Hugh Miller said the only school in which he was properly taught was "that world-wide school in which toil and hardship are the severe but noble teachers." He who allows his application to falter, or shirks his work on frivolous pretexts, is on the sure road to ultimate failure. Let any task be undertaken as a thing not possible to be evaded, and it will soon come to be performed with alacrity and cheerfulness. Charles IX of Sweden was a firm believer in the power of will, even in youth. Laying his hand on the head of his youngest son when engaged on a difficult task, he exclaimed, "He shall do it! he shall do it!"

The habit of application becomes easy in time, like every other habit. Thus persons with comparatively moderate powers will accomplish much, if they apply themselves wholly and indefatigably to one thing at a time. Fowell Buxton placed his confidence in ordinary means and extraordinary application; realizing the Scriptural injunction, "Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might;" and he attributed his own success in life to his practice of "being a whole man to one thing at a time."

"Where there is a will there is a way," is an old and true saying. He who resolves upon doing a thing, by that very resolution often scales the barriers to it, and secures its achievement. To think we are able, is almost to be so—to determine upon attainment is frequently attainment itself. Thus, earnest resolution has often seemed to have about it almost a savor of omnipotence. The strength of Suwarrow's character lay in his power of willing, and, like most resolute persons, he preached it up as a system. "You can only half will," he would say to people who failed. Like Richelieu and Napoleon, he would have the word "impossible" banished from the dictionary. "I don't know," "I can't," and "impossible," were words which he detested above all others. "Learn! Do! Try!" he would exclaim. His biographer has said of him, that he furnished a remarkable illustration of what may be effected by the energetic development and exercise of faculties the germs of which at least are in every human heart.

One of Napoleon's favorite maxims was, "The truest wisdom is a resolute determination." His life, beyond most others, vividly showed what a powerful and unscrupulous will could accomplish. He threw his whole force of body and mind direct upon his work. Imbecile rulers and the nations they governed went down before him in succession. He was told that the Alps stood in the way of his armies. "There shall be no Alps," he said, and the road across the Simplon was constructed, through a district formerly almost inaccessible. "Impossible," said he, "is a word only to be found in the dictionary of fools." He was a man who toiled terribly; sometimes employing and exhausting four secretaries at a time. He spared no one, not even himself. His influence inspired other men, and put a new life into them. "I made my generals out of mud" he said. But all was of no avail; for Napoleon's intense selfishness was his ruin, and the ruin of France, which he left a prey to anarchy.

Before the man resolutely impelled to action by singleness of purpose, every obstacle disappears as he approaches, and every lesson of experience becomes the stepping-stone to further victories in the same direction.

It is this singleness of purpose, this absorption in a great life work, that nerves our missionaries in their exile. A splendid example of this is presented in the career of the great missionary and explorer, Dr. Livingstone.

He has told the story of his life in that modest and unassuming manner which is so characteristic of the man himself. His ancestors were poor but honest Highlanders, and it is related of one of them, renowned in his district for wisdom and prudence, that when on his death-bed, he called his children round him and left them these words, the only legacy he had to bequeath: "In my lifetime," said he, "I have searched most carefully through all the traditions I could find of our family, and I never could discover that there was a dishonest man among our forefathers; if, therefore, any of you, or any of your children, should take to dishonest ways, it will not be because it runs in our blood; it does not belong to you: I leave this precept with you—Be honest." At the age of ten, Livingstone was sent to work in a cotton factory near Glasgow as a "piecer." With part of his first week's wages he bought a Latin grammar, and began to learn that language, pursuing the study for years at a night-school. He would sit up conning his lessons till twelve or later, when not sent to bed by his mother, for he had to be up and at work in the factory every morning by six. In this way he plodded through Virgil and Horace, also reading extensively all books, excepting novels, that came in his way, but more especially scientific works and books of travels. He occupied his spare hours, which were but few, in the pursuit of botany, scouring the neighborhood to collect plants. He even carried on his reading amidst the roar of the factory machinery, so placing the book upon the spinning-jenny which he worked, that he could catch sentence after sentence as he passed it. In this way the persevering youth acquired much useful knowledge; and as he grew older, the desire possessed him of becoming a missionary to the heathen. With this object he set himself to obtain a medical education, in order the better to be qualified for the work. He accordingly economized his earnings, and saved as much money as enabled him to support himself while attending the Medical and Greek classes as well as the Divinity Lectures, at Glasgow, for several winters, working as a cotton-spinner during the remainder of each year. He thus supported himself, during his college career, entirely by his own earnings as a factory workman, never having received a farthing of help from any other source. "Looking back now," he honestly said, "at that life of toil, I cannot but feel thankful that it formed such a material part of my early education; and, were it possible, I should like to begin life over again in the same lowly style, and to pass through the same hardy training." At length he finished his medical curriculum, wrote his Latin thesis, passed his examinations, and was admitted a licentiate of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons. At first he thought of going to China, but the war then waging with that country prevented his following out the idea; and having offered his services to the London Missionary Society, he was by them sent out to Africa, which he reached in 1840. He had intended to proceed to China by his own efforts; and he says the only pang he had in going to Africa at the charge of the London Missionary Society was, because "it was not quite agreeable to one accustomed to worked his own way to become, in a manner, dependent upon others." Arrived in Africa, he set to work with great zeal. He could not brook the idea of merely entering upon the labors of others, but cut out a large sphere of independent work, preparing himself for it by undertaking manual labor in building and other handicraft employment, in addition to teaching, which, he says, "made me generally as much exhausted and unfit for study in the evenings as ever I had been when a cotton-spinner." Whilst laboring amongst the Bechuanas, he dug canals, built houses, cultivated fields, reared cattle, and taught the natives to work as well as to worship. When he first started with a party of them on foot upon a long journey, he overheard their observations upon his appearance and powers. "He is not strong," said they; "he is quite slim, and only appears stout because he puts himself into those bags (trousers): he will soon knock up." This caused the missionary's Highland blood to rise, and made him despise the fatigue of keeping them all at the top of their speed for days together, until he heard them expressing proper opinions of his pedestrian powers. What he did in Africa, and how he worked, may be learnt from his own "Missionary Travels," one of the most fascinating books of its kind that has ever been given to the public. One of his last known acts is thoroughly characteristic of the man. The "Birkenhead" steam launch, which he took out with him to Africa, having proved a failure, he sent home orders for the construction of another vessel at an estimated cost of 2,000 pounds. This sum he proposed to defray out of the means which he had set aside for his children, arising from the profits of his books of travel. "The children must make it up themselves," was in effect his expression in sending home the order for the appropriation of the money.

The career of John Howard was throughout a striking illustration of the same power of patient purpose. His sublime life proved that even physical weakness could remove mountains in the pursuit of an end recommended by duty. The idea of ameliorating the condition of prisoners engrossed his whole thoughts, and possessed him like a passion; and no toil, or danger, nor bodily suffering could turn him from that great object of his life. Though a man of no genius and but moderate talent, his heart was pure and his will was strong. Even in his own time he achieved a remarkable degree of success; and his influence did not die with him, for it has continued powerfully to affect not only the legislation of his own country, but of all civilized nations, down to the present hour.

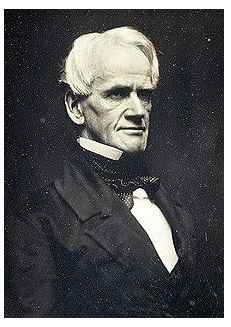

Horace Mann, famous as a teacher and reformer in his day, was urged

by his friends in Ohio to go to Congress. He replied: "I have a great

deal of respect for men in public life, but I have more respect for

my on life-work. If I know anything, it is the science or art of

teaching, and to this work, please God, I shall devote the whole of

my life." And he kept his word.

Horace Mann, famous as a teacher and reformer in his day, was urged

by his friends in Ohio to go to Congress. He replied: "I have a great

deal of respect for men in public life, but I have more respect for

my on life-work. If I know anything, it is the science or art of

teaching, and to this work, please God, I shall devote the whole of

my life." And he kept his word.

Singleness of purpose implies firmness, for in this day of change and speculation, the young man who has saved up a little money, hoping one day to go into business for himself, will find on every hand temptations to invest in enterprises of which he knows nothing. Here his resolution will be tested. Remember there is no element of human character so potential for weal or woe as firmness. To the merchant and the man of business it is all-important. Before its irresistible energy the most formidable obstacles become as cobweb barriers in its path. Difficulties, the terror of which causes the timid and pampered sons of luxury to shrink back with dismay, provoke from the man a lofty determination only a smile. The whole history of our race—all nature, indeed—teems with examples to show what wonders may be accomplished by resolute perseverance and patient toil.

It is related of Tamerlane, the terror of whose arms spread through all the Eastern nations, and whom victory attended at almost every step, that he once learned from an insect a lesson of perseverance, which had a striking effect on his future character and success.

When closely pursued by his enemies, as a contemporary writer tells the incident, he took refuge in some old ruins, where left to his solitary musings, he espied an ant tugging and striving to carry a single grain of corn. His unavailing efforts were repeated sixty-nine times, and at each brave attempt, as soon as he reached a certain point of projection, he fell back with his burden, unable to surmount it; but the seventieth time he bore away his spoil in triumph, and left the wondering hero reanimated and exulting in the hope of future victory.

How pregnant the lesson this incident conveys! How many thousand instances there are in which inglorious defeat ends the career of the timid and desponding, when the same tenacity of purpose would crown it with triumphant success.

Resolution is almost omnipotent. It was well observed by a heathen moralist, that it is not because things are difficult that we dare not undertake them. Be, then, bold in spirit. Indulge no doubts. Shakespeare says truly and wisely—

"Our doubts are traitors,

And make us lose the good we oft might win,

By fearing to attempt."

In the practical pursuit of our high aim, let us never lose sight of it in the slightest instance; for it is more by a disregard of small things, than by open and flagrant offenses, that men come short of excellence. There is always a right and a wrong; and, if you ever doubt, be sure you take not the wrong. Observe this rule, and every experience will be to you a means of advancement.

A Review of "How to Get On in Life"

Table of Contents

Chapter XX - Business and Brains

OTHER WEBSITES ON SUCCESS:

Law of Attraction Articles