[380]

CHAPTER XII

ST. PAUL AT PUTEOLI

The Gospel first came to Europe in circumstances similar to those in which it came into human history. Through poverty, shame, and

suffering - through the manger, the cross, and the sepulchre - did our Saviour accomplish the salvation of the world; through stripes and

imprisonment, through the gloom of the inner dungeon and the pain and shame of the stocks, did Paul and Silas declare at Philippi the glad

tidings of salvation. Out of the midnight darkness which enveloped the apostles of the Cross, as they sang in the prison, came the marvellous

light that was destined to illumine all Europe. Out of the stocks which held fast the feet that came to the shores of the West shod with

the preparation of the gospel of peace, to proclaim deliverance to the captives, sprang that glorious liberty which has broken every fetter

that bound the bodies and souls of men throughout Christendom. After the earthquake that shook the prison walls and released the prisoners

came the still, small voice of power, which overthrew the tyrannies and superstitions of ages, and remade society from its very foundations.

Very similar were the circumstances in which the apostle landed at the quay of Puteoli. A weary, worn-out prisoner, accused by his own

countrymen, on his way to be judged at the tribunal of the Roman emperor, associated with a troop of malefactors, St. Paul

disembarked,[381] on the 3d of May of the year 59, from the ship Castor

and Pollux, after having gone through storm and shipwreck, and first touched the shore of the wonderful land destined afterwards to be the

scene of the mightiest triumphs of the Gospel, and the most enlightened centre for its diffusion throughout the world. Like the

birth of Rome itself, whose obscure foundation, according to the beautiful myth, was laid by the outcast son of a Vestal Virgin, the

kingdom of the despised virgin-born Jesus of Nazareth that cometh not with observation, stole unawares, amid the meanest circumstances, into

the very heart of the Roman world.

Very similar were the circumstances in which the apostle landed at the quay of Puteoli. A weary, worn-out prisoner, accused by his own

countrymen, on his way to be judged at the tribunal of the Roman emperor, associated with a troop of malefactors, St. Paul

disembarked,[381] on the 3d of May of the year 59, from the ship Castor

and Pollux, after having gone through storm and shipwreck, and first touched the shore of the wonderful land destined afterwards to be the

scene of the mightiest triumphs of the Gospel, and the most enlightened centre for its diffusion throughout the world. Like the

birth of Rome itself, whose obscure foundation, according to the beautiful myth, was laid by the outcast son of a Vestal Virgin, the

kingdom of the despised virgin-born Jesus of Nazareth that cometh not with observation, stole unawares, amid the meanest circumstances, into

the very heart of the Roman world.

Momentous events were taking place at the time throughout the Roman Empire, attracting all eyes, and

engaging the attention of all minds; but the unnoticed landing at

Puteoli of the humble Jewish prisoner, judging by its marvellous

results, was by far the most important. It marked a new era in the

history of the world. And there was something significant in the

coincidence that St. Paul should have come to the Italian shore in the

ship Castor and Pollux, the names not merely of the patrons of

sailors, but also of the saviours of Rome. The mighty empire which

human tyranny had established has crumbled to pieces, and we walk

to-day amid its ruins; but the kingdom of peace and righteousness

which Paul came to inaugurate has spread from that coign of vantage

over all the earth, and in a world of death and change has impressed

upon the minds of men with a new force the idea of the eternal and the

unchangeable.

Earth holds no fairer scene than that which met the apostle's gaze as he entered the bay of Puteoli. "See Naples, and die," is the cuckoo

cry of the modern tourist who visits this enchanted region; and such a vision is indeed worthy to be the last imprinted upon a human retina.

It is called by the Italians themselves "Un pezzo di cielo caduto in

terra," a piece of heaven fallen upon earth. Shores that curve in

every line of beauty, holding out arm-like promontories, into whose

embrace the tideless[382] sea runs up; mountain-ranges whose tops in

winter are covered with snow, and whose sides are draped with the

luxuriant vegetation of the South; a large city rising in a series of

semicircular terraces from the deep azure of the sea to the deep azure

of the mountains, whose eastern architecture flushes to a vivid rosy

hue in the afternoon light like some fabled city of the poets; and

dominating the glorious horizon the double peak of Vesuvius forming

the centre in which all the features of landscape loveliness are

focussed—crowned by its pillar of cloud by day and of fire by night.

Such is the picture upon which travellers crowd from the ends of the

earth to gaze.

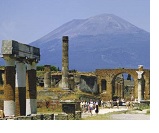

Nor was the view different in its most important elements in the days

of the apostle. The same great forms of the landscape met the eye; and

the same magic play of light and colour, the same jewel-points

flashing in the waters, the same gleams of purple and crimson

wandering over town, and vineyard, and wood, transfigured the scene

then, which gives it more than half its loveliness now. But its human

elements were different. Swarming with life as are these shores at the

present day, they were even more populous then. Where we now wander

through picturesque ruins and silent solitudes, prosperous towns and

villages stood; and temples, palaces, and summer houses of patrician

magnificence crowded upon each other to such an extent that the sea

itself was invaded, and an older Venice rose from the waters along the

curves of its bays. The shores of Baiæ were the very centre of Roman

splendour. The emperor and his court spent a large part of the year

there; and noble families, that elsewhere had domains miles in extent,

were there satisfied with the smallest space upon which they could

build a house and plant a garden. Pompeii and Herculaneum, in all

their reckless gaiety, lay, unconscious of danger, at the foot of

Vesuvius, then a grassy mountain wooded to the summit with oak and

chestnut, and known from time immemorial as a field of pasture for

flocks and herds. [383]

Nor was the view different in its most important elements in the days

of the apostle. The same great forms of the landscape met the eye; and

the same magic play of light and colour, the same jewel-points

flashing in the waters, the same gleams of purple and crimson

wandering over town, and vineyard, and wood, transfigured the scene

then, which gives it more than half its loveliness now. But its human

elements were different. Swarming with life as are these shores at the

present day, they were even more populous then. Where we now wander

through picturesque ruins and silent solitudes, prosperous towns and

villages stood; and temples, palaces, and summer houses of patrician

magnificence crowded upon each other to such an extent that the sea

itself was invaded, and an older Venice rose from the waters along the

curves of its bays. The shores of Baiæ were the very centre of Roman

splendour. The emperor and his court spent a large part of the year

there; and noble families, that elsewhere had domains miles in extent,

were there satisfied with the smallest space upon which they could

build a house and plant a garden. Pompeii and Herculaneum, in all

their reckless gaiety, lay, unconscious of danger, at the foot of

Vesuvius, then a grassy mountain wooded to the summit with oak and

chestnut, and known from time immemorial as a field of pasture for

flocks and herds. [383]

The Bay of Misenum, now so solitary that the scream of the sea-fowl is almost the only sound that breaks the stillness,

was crowded with the vessels of the Roman fleet, commanded by Pliny; and its waters were alive with the pleasure-boats of the patrician

youths, filling the air with the music of their laughter and song. Puteoli, or, as it is now called, Pozzuoli, a dull and stagnant

fourth-rate town, was then the Liverpool of Italy, carrying on an immense trade in corn between Egypt and the western provinces of the

Roman Empire. It rivalled Delos in magnificence, and was called the Little Rome. It had a splendid forum and harbour, and was guarded by

fortifications which resisted the repeated attacks of Hannibal.

In this region almost every famous Roman of the later days of the

Republic and the earlier days of the Empire had his sea-side villa to

which he retired from the noise and bustle of the Imperial City. It

was the Brighton or more properly the Bath of Rome; for though it was

frequented during the burning heats of summer for the sake of its

comparative coolness, it was principally chosen as a winter retreat to

escape from the frosts and snows of the north.

Lucullus carried here the gorgeous luxury and extravagance of his city life; here Augustus

and Hadrian had their palaces erected on vast piers thrown out into

the sea, whose waters still murmur over their remains; while Cicero

built here his Puteolanum, delightfully situated on the coast, and

surrounded by a shady grove, which he called his Academy, in imitation

of Plato, and where he composed his "Academia" and "De Fato." Hardly

an inch of the soil but is full of fragments of mosaic pavements. The

common stones of the road are often rich marbles, that formed part of

imperial structures; and the very dust on which you tread, if

analysed, would be found to be a powder of gems and precious stones.

Lucullus carried here the gorgeous luxury and extravagance of his city life; here Augustus

and Hadrian had their palaces erected on vast piers thrown out into

the sea, whose waters still murmur over their remains; while Cicero

built here his Puteolanum, delightfully situated on the coast, and

surrounded by a shady grove, which he called his Academy, in imitation

of Plato, and where he composed his "Academia" and "De Fato." Hardly

an inch of the soil but is full of fragments of mosaic pavements. The

common stones of the road are often rich marbles, that formed part of

imperial structures; and the very dust on which you tread, if

analysed, would be found to be a powder of gems and precious stones.

But alas! in some of the fairest spots of earth man has been vilest; and like the ancient Cities of the Plain, which stood in a region of

Edenic loveliness, the shores[384] of the Bay of Naples were inhabited by

a race corrupted with the worst vices of Roman civilisation. Some of the most dreadful crimes that have disgraced humanity were committed

on that radiant shore. Yonder sleeps in the azure distance the enchanted isle of Capri, haunted for ever by dreadful memories of the

unnameable atrocities with which the Emperor Tiberius had stained its peaceful bowers. On the neighbouring heights of Posilipo are traces of

the villa of Vedius, and of the celebrated fish-ponds where he fed his murenę with the flesh of his disobedient slaves. On the shore of

Puteoli the apostle might have seen the remains of one of the maddest freaks of imperial folly—the floating-bridge of Caligula, stretching

across the bay for nearly three miles, and decorated with the finest mosaic pavements and sculpture. Over this useless bridge the insane

emperor drove in the chariot and armour of Alexander the Great, to celebrate his triumph over the Parthians; and from it, on his return,

he ordered the crowd of inoffensive spectators to be hurled into the sea. By withdrawing for the construction of this bridge the ships

employed in the harbour, the importation of corn was put a stop to, and a grievous famine, felt even in Rome, was the result. And near at

hand was Bauli, where Nero...the very Cęsar to whom it is startling to remember that St. Paul appealed, and before whom he was going to be

judged,—only two years before attempted the murder of his own mother, Agrippina, which failed because of her discovery of the plot, but

which was most ruthlessly accomplished very soon afterwards.

Here too Marcellus was poisoned by Livia, that Tiberius might ascend the throne of Augustus; and Domitian by Nero, that he might enjoy the wealth of

his aunt. Here Hadrian, a few days before his own miserable end, compelled his beautiful and accomplished wife, Sabina, to put herself

to death, that she might not survive him in such a wretched world. And in the cities at the foot of Vesuvius have been revealed to us, after

nature had kindly hidden them for eighteen centuries, tokens of a[385]

depravity so utter, that we cannot help looking upon the fiery deluge from the mountain, that soon after St. Paul's visit swept them out of

existence, as a Divine judgment like that of Sodom and Gomorrha. And darker even than these monstrosities of wickedness was the divine

worship paid on these shores to the Roman emperors. It was a pitiable spectacle when the sailors of an Alexandrian ship, coming into the

harbour of Puteoli, gave thanks for their prosperous voyage to the dying Augustus, whom they met cruising on the waters vainly in search

of health, and offered him divine honours, which the gratified emperor accepted, and rewarded with gifts.

But what shall we think of the worship of the god Caligula and the god Nero?

Surely a people who could raise altars and offer sacrifices to such unmitigated monsters

must have lost the very conception of religion. Not only virtue, but the very belief in any source of virtue, must have been utterly

extirpated in them. When Herod spoke, the people said it was the voice of God; and he was smitten with worms because he gave not God the

glory. And surely the superhuman wickedness of the Cęsars may be regarded as a punishment, equally significant, of the fearful

blasphemy of the worshipped and the worshippers.

No wonder that the shores of Baię now present a picture of the saddest desolation. Where man sins, there man suffers. The relation between

human crime and the barren wilderness is still as inflexibly maintained as at the first. Until all recollection of the iniquities

of the place has passed away it is fitting that these silent shores should remain the desert that they are. We should not wish the old

voluptuous magnificence revived; and these myrtle bowers can never more regain the charm of virgin solitudes untainted by man. Italy,

like Palestine, has thus an accursed spot in its fairest region...a visible monument to all ages, of the great truth that the tidal wave

of retribution will inevitably overwhelm every nation that forgets the eternal distinctions of right and wrong.

St. Paul was a man of keen sensibilities and strong[386] imagination. He

must therefore at Puteoli have been deeply impressed at once with the

loveliness of nature and the wickedness of man. The contrast would

present itself to him in a very painful manner. As at Athens...where

his spirit was moved within him when he saw the city wholly given up

to idolatry...so here he must have had that noble indignation against

the iniquities of the place...the outrages committed on the laws of

God, and the dishonour done to the nature of man made in the Divine

image—to which David and Jeremiah, and all the loftiest spirits of

mankind, have given such stern and yet patriotic utterance. What

others were callous to, filled him with keen shame and sorrow. He who

could have wished that himself were accursed from Christ for his

brethren, his kinsmen according to the flesh, must have had a profound

pity for these wretched victims of profligacy, who were looking in

their ignorance for salvation to a brutal mortal worse than

themselves,—"the son of perdition, sitting in the temple of God,

showing that he was God." And to this feeling of indignation and

sorrow, because of the wickedness of the place, must have been added a

feeling of personal despondency. From the significant circumstance

that the apostle thanked God, and took courage, when he met the

Christian brethren at Apii Forum, we may infer that he had previously

great heaviness of spirit. He would be more or less than human, if on

setting his foot for the first time on the native soil of the

conquerors of his country, and the lords of the whole world, and

seeing on every side, even at this distance from the imperial city,

overwhelming evidences of the luxury and power of the empire, he did

not feel oppressed with a sense of personal insignificance. Evil had

throned itself there on the high places of the earth, and could mock

at the puny efforts of the followers of Jesus to cast it down.

Idolatry had so deeply rooted itself in the interests and passions of

men which were bound up in its continuance, that it seemed a foolish

dream to expect that it would be supplanted by[387] the preaching of the

Cross, which to St. Paul's own people was a stumbling-block and to all

other nations foolishness. And who was he that he should undertake

such a mission—a weak and obscure member of a despised race, a

prisoner chained to a soldier, appealing to Cæsar against the

condemnation of his own countrymen. We can well believe, that

notwithstanding the sustaining grace that was given to him, the heart

of the apostle must have been very heavy when he stood in the midst of

the jostling crowd on the quay of Puteoli, and took the first step

there on Italian soil of his journey to Rome. He felt most keenly all

that a man can feel of the shame and offence of the Cross; but

nevertheless he was not ashamed of the Gospel of Christ. And his

presence there on that Roman quay—a despised prisoner in bonds for

the sake of the Gospel—is a picture, that appeals to every heart, of

the triumph of Divine strength in the midst of human weakness; and a

most striking proof, moreover, that not by might, but by the Spirit of

love, does God bring down the strongholds of sin.

But God furnished a providential cure for whatever despondency the

apostle may have felt. No sooner did he land than he found himself

surrounded by Christian brethren, who cordially welcomed him, and

persuaded him to remain with them seven days. Such brotherly kindness

must have greatly cheered him; and the week spent among these loyal

followers of the Lord Jesus must have been a time of bodily and

spiritual refreshment opportunely fitting him for the trying

experiences before him. Doubtless these brethren were Jewish converts

to the Christian faith; for that there were Jewish residents at

Puteoli, residing in the Tyrian quarter of the city, we are assured by

Josephus; and this we should have expected from the mercantile

importance of the place and its intimate commercial relations with the

East. How they came under the influence of the Gospel we know not;

they may have been among "the strangers of Rome" who came to Jerusalem

at Pentecost to keep the[388] national feasts in obedience to the Mosaic

Law, and who were then brought to the knowledge of the truth by the

preaching of St. Peter; or perhaps they were converts of St Paul's own

making, in some of the numerous places which he visited on his

missionary tours, and who afterwards came to reside for business

purposes at this port. We see in the presence of the Jewish brethren

at Puteoli one of the most striking illustrations of the providential

pre-arrangements made for the diffusion of the Gospel throughout all

nations. The Jews had a more than ordinary attachment to their native

land. Patriotism in their case was not only a passion, but a part of

their religion; and their love of country was entwined with the

holiest feelings of their nature. In Jerusalem alone could God be

acceptably worshipped. And yet it was divinely ordered that those who

had been for ages the hermits of the human race should become all at

once the most cosmopolitan, when the time for imparting to the world

the benefits of their isolated religious training had come. And the

Jews thus scattered abroad preserved amid their alien circumstances

their national worship and customs, and thus became the natural links

of connection between the missionaries of the Cross and the Gentiles

whom they wished to reach. Through such Jewish channels the Gospel

speedily penetrated into remote localities, which otherwise it would

have taken a long time to reach. We are struck with distinct traces of

the Christian faith in the time of St. Paul in the most unexpected

places. For instance, in the National Museum at Naples I have seen

rings with Christian emblems engraved upon them, which were found at

Pompeii; proving beyond doubt that there had been followers of Jesus

even in that dissolute place, who, unlike Lot and his household, were

overwhelmed in the same destruction with those whose evil deeds must

have daily vexed their righteous souls. The same symbols which we find

in the Roman Catacombs,...the palm branch, the sacred fish the monogram

of Jesus, the dove, are unmistakably repre[389]sented on these rings. Some

of them are double, indicating that they were used by married persons:

one has the palm branch twice repeated; another exhibits the palm and

anchor; a third has a dove with a twig in its bill; and one ring has

the Greek word elpis—hope—inscribed upon it.

St. Paul at Puteoli may be said to have dwelt among his own people.

Not only was he with his own countrymen and fellow-disciples, but he

was in the midst of associations that forcibly recalled his home. The

apostle was a citizen of a Greek city, and the language in which he

spoke was Greek; and here, in the Bay of Naples, he was in the midst

of a Greek colony, where Roman influence had not been able to efface

the deep impression which Greece had made upon the place. The original

name of the splendid expanse of water before him was the Bay of Cumæ;

and Cumæ was absolutely the first Greek settlement in the western

seas. Neapolis or Parthenope was the beautiful Greek name of the city

of Naples, testifying to its Hellenic origin; and Dicæarchia was the

older Greek name of Puteoli, a name used to a late period in

preference to its Latin name, derived from the numerous mineral

springs in the neighbourhood. The whole lower part of Italy was wholly

Greek; its arts, its customs, its literature, were all Hellenic; and

its people belonged to the pure Ionic race whose keen imaginations and

vivid sensuousness seemed to have been created out of the fervid hues

and the pellucid air of their native land. Everywhere the subtle Greek

tongue might be heard; and all, so far as Greek influence was

concerned, was as unchanged in the days of the apostle as when

Pythagoras visited the region, and adopted the inhabitants as the

fittest agents in his great scheme of universal regeneration. St. Paul

therefore, at Puteoli, might have imagined himself standing on the

very soil of classic Hellas, and felt as much at home as in his own

native city of Tarsus. This wide diffusion of the Greek language

throughout the West as well as the[390] East at this time is another of

the remarkable providential pre-arrangements which prepared the way

for the preaching of the Gospel throughout the world. A Gentile

speech, by a series of wonderful events, was thus made ready over all

the world to receive and to communicate the glorious Gospel that was

to be preached to all nations.

The remains of the ancient pier upon which St. Paul landed may still

be seen. Indeed, no Roman harbour has left behind such solid

memorials. No less than thirteen of the buttresses that supported its

arches are left, three lying under water; all constructed of brick

held together by that Roman cement called pozzolana, after the town of

Pozzuoli, whose extraordinary tenacity rivals that of the living rock.

You can plant your feet upon the very stones upon which the apostle

must have stood. And if you happen to be there on the 3d of May you

will see a solemn procession of the inhabitants of the decayed town,

headed by their priests, celebrating the anniversary of this memorable

incident. The first conspicuous object upon which the eye of the

apostle would rest on landing would be the Temple of Neptune, of which

a few pillars are still standing in the midst of the water. Here

Caligula, in his mad passage over his bridge of boats, paused to offer

propitiatory sacrifices. Here, too, Cæsar, before he sailed to Greece

to encounter the forces of Antony at Actium, sacrificed to Neptune;

and here the crew of every ship presented offerings, in order to

secure favouring winds and waves when outward bound, or in gratitude

when returning home from a successful voyage.

Beyond this he would see in all its splendour the famous bathing establishment built over a

thermal spring near the sea, which has since been known as the Temple

of Serapis, an Egyptian deity, whose worship had spread widely in

Italy. Three tall columns of cipollino marble, belonging to the

portico of this building, are still standing, with their bases under

water; and they have acquired a world-wide interest, especially to

geologists, as records of the successive elevations and depres[391]sions

of the coast-line during the historical period; these changes being

indicated on their shafts by the different watermarks and the

perforations of marine bivalves or boring-shells well known to be

living in the Mediterranean Sea. In the upper part of the town, on a

commanding height, he would behold the Temple of Augustus, built for

the worship of the deified founder of the Roman Empire. A Christian

cathedral dedicated to St. Proculus, who suffered martyrdom in the

same year with St. Januarius, containing the tomb of Pergolesi, the

celebrated musical composer, now occupies the site of the pagan

shrine, and has six of its Corinthian pillars, that looked down upon

the apostle as he landed, built into its walls.

Beyond this he would see in all its splendour the famous bathing establishment built over a

thermal spring near the sea, which has since been known as the Temple

of Serapis, an Egyptian deity, whose worship had spread widely in

Italy. Three tall columns of cipollino marble, belonging to the

portico of this building, are still standing, with their bases under

water; and they have acquired a world-wide interest, especially to

geologists, as records of the successive elevations and depres[391]sions

of the coast-line during the historical period; these changes being

indicated on their shafts by the different watermarks and the

perforations of marine bivalves or boring-shells well known to be

living in the Mediterranean Sea. In the upper part of the town, on a

commanding height, he would behold the Temple of Augustus, built for

the worship of the deified founder of the Roman Empire. A Christian

cathedral dedicated to St. Proculus, who suffered martyrdom in the

same year with St. Januarius, containing the tomb of Pergolesi, the

celebrated musical composer, now occupies the site of the pagan

shrine, and has six of its Corinthian pillars, that looked down upon

the apostle as he landed, built into its walls.

A temple of Diana and a temple of the Nymphs also adorned the town, from which numerous

columns and sculptures have been recently recovered. On every side the

apostle would see mournful tokens that the city was wholly given up to

idolatry, - to the worship of mortal men and an ignoble crowd of gods

and goddesses borrowed from all nations; and yet he had equally sad

proofs that the idolatry was altogether a hollow and heartless

pretence, - that the superstitious creed publicly maintained by the

city had long ceased to command the respect of its recognised

defenders.

I walked up from the town along the remains of the Via Campana, a

cross-road that led from Puteoli to Capua and there joined the famous

Appian Way. Along this road the apostle passed on his way to Rome; and

it is still paved with the original lava-blocks upon which his feet

had pressed. One of the principal objects on the way is the

amphitheatre of Nero, with its tiers of seats, its arena, and its

subterranean passages, in a wonderful state of preservation, richly

plumed with the delicate fronds of the maiden-hair fern, which drapes

with its living loveliness so many of the ruins of Greece and Italy.

It was here that Nero himself rehearsed the parts in which he wished

to act on the more public stage of Rome. The sands of the arena were

dyed with the[392] blood of St. Januarius, who was thrown to the wild

beasts by order of Diocletian, and whose blood is annually liquefied

by a supposititious miracle in Naples at the present day. Behind the

amphitheatre the apostle would get a glimpse of the famous Phlegræan

Fields so often referred to in the classic poets as the scene of the

wars of the gods and the giants.

This is the Holy Land of Paganism. All the scenery of the eleventh

book of the Odyssey and of the sixth book of the Æneid spreads

beneath the eye. At every step you come upon some spot associated with

the romantic literature of antiquity. From thence the imaginative

shapes of Greek mythology passed into the poetry of Rome. There

everything takes us back far beyond the birth of Roman civilisation,

and reminds us of the legends of the older Hellenic days, which will

exercise an undying spell on the higher minds of the human race down

to the latest ages. It is the land of Virgil, whose own tomb is not

far off; and under the guidance of his genius we visit the ghostly

Cimmerian shores, now bathed in glowing sunshine, and stand on spots

that thrilled the hearts of Hercules and Ulysses with awe. There the

terrible Avernus, to which the descent was so easy, sleeps in its deep

basin, long ago divested by the axe of Agrippa of the impenetrable

gloom and mysterious dread which its dark forests had created; its

steep banks partly covered with natural copsewood bright with a living

mosaic of cyclamens and lilies, and partly formed of cultivated

fields. During my visit the delicious odour of the bean blossom

pervaded the fields, reminding me vividly of familiar rural scenes far

away. Yonder is the subterranean passage called by the common people

the Sibyl's Cave, where Æneas came and plucked the golden bough, and,

led by the melancholy priestess of Apollo, went down to the dreary

world of the dead. It was the general tradition of Pagan nations that

the point of departure from this world, as well as the entrance to the

next, was always in the west. We find the largest[393] number of the

prehistoric relics of the dead on the western shores of our own

country. The cave of Loch Dearg—at first connected with primitive

pagan rites and subsequently the traditional entrance to the Purgatory

of St. Patrick—is situated in the west of Ireland, and corresponds to

the cave of the Sibyl and the Lake of Avernus in Italy. Indeed the

word Avernus itself bears such a close resemblance to the Gaelic word

Ifrinn—the name of the infernal regions, and to the name of Loch

Hourn, the Lake of Hell, on the north-west coast of Scotland—that it

has given rise to the supposition that it was the legacy of a

prehistoric Celtic people who at one time inhabited the Phlegræan

Fields. On the other side of Lake Avernus is the Mare Morto, the Lake

or Sea of the Dead, with its memories of Charon and his ghostly crew,

which now shines in the setting sun like a field of gold sparkling

with jewels; and beyond it are the Elysian Fields, the abodes of the

blessed, the rich life of whose soil breaks out at every pore into a

luxuriant maze of vines and orange trees, and all manner of lovely and

fruitful vegetation. Still farther behind is the Acherusian Marsh of

the poets, now called the Lake of Fusaro, because hemp and flax are

put to steep in it; and the river Styx itself, by which the gods dare

not swear in vain, reduced to an insignificant rill flowing into the

sea. It is most interesting to think of the apostle Paul being

associated with this enchanted region. His presence on the scene is

necessary to complete its charm, and to remind us that the vain dreams

of those blind old seekers after God were all fulfilled in Him who

opened a door for us in heaven, and brought life and immortality to

light in the Gospel.

St. Paul must have noticed—though Scripture, intent only upon the

unfolding of the religious drama, makes no reference to it—the crater

of Solfatara, one of the most wonderful phenomena of this wonderful

region, for it lay directly in his path, and was only about a mile

distant from Puteoli. This was the famous Forum of[394] Vulcan, where the

god fashioned his terrible tools, and shook the earth with the fierce

fires of his forge. On account of its gaseous fumaroles, and the

flames thrown out with a loud roaring noise from one gloomy cavern in

its side, this volcano may still be considered active. Its white

calcined crater is clothed in some places with green shrubs,

particularly with luxuriant sage, myrtle, and white heather; but an

eruption took place in it so late as 1198, during which a lava

current, a rare phenomenon in this district, flowed from its southern

edge to the sea, destroying the ancient cemetery on the Via Puteolana,

and forming the present promontory of Olibano. The ground sounds

hollow beneath a heavy tread, reminding one unpleasantly that but a

thin crust covers the fiery abyss which might break through at any

moment. With the exception of Vesuvius, this is the only surviving

remnant of the fierce elemental forces which have devastated this

coast in every direction. The whole region is one mass of craters of

various sizes and ages, some far older than Vesuvius, and others of

comparatively recent origin. They are all craters of eruption and not

of elevation; and in their formation they have interfered with and in

some cases almost obliterated pre-existing ones. Some of them are

filled with lakes, and others clothed with luxuriant vineyards, and

wild woods fit for the chase, or encircling cultivated fields. To one

looking upon it from a commanding position such as the heights of

Posilipo, the landscape presents a universally blistered appearance.

Hot mineral springs everywhere abound, often associated with the ruins

of old Roman baths; and the soil is a white felspathic ash, disposed

in layers of such fineness and regularity that they look as if they

had been stratified under water, the sea and the shore having

alternately given place to each other. Of the white earth abounding on

every side, which has given to the place the old name of Campi

Leucogæi, and is the result of the metamorphosis of the trachytic tufa

by the chemical action of the gases that rise up through the

fumaroles, a very[395] fine variety of porcelain—known to collectors as

Capo di Monti—used to be made on the hill behind Naples, and it has

been supposed that the china clays of Cornwall and other places have

been produced from the felspars of the granites in a similar way. The

whole of the Solfatara crater has been enclosed for the purpose of

manufacturing alum from its soil. On the hillside to the north there

are several caverns, called stufe, from whence gas and hot steam

arise, and these are used by the inhabitants as admirable vapour

baths. So late as the year 1538 a terrible volcanic explosion,

accompanied with violent earthquakes, happened not far from Puteoli,

which threw up from the flat plain on which the village of Tripergola

stood, a mountain called Monte Nuovo, four hundred and forty feet high

and a mile and a half in circumference, consisting entirely of ashes

and cinders, obliterating a large part of the celebrated Leucrine

Lake, elevating the site of the temple of Serapis sixteen feet, and

then depressing it, and generally changing the old features of this

locality. This eruption gave relief to the throes of Lake Avernus,

which henceforth ceased to send forth its exhalations, and became the

cheerful garden scene which we now behold.

Here on a small scale, in the very neighbourhood of man's busiest

haunts, occur the cosmical cataclysms which are usually seen only in

remote solitudes, and which during the unknown ages of geology have

left their indelible records on large portions of the earth's surface.

Here we are admitted into the very workshop of Nature, and are

privileged to witness her processes of creation. In the neighbourhood

of Rome the volcanoes are long extinct. Nature is dead, and there is

nothing left but her cold gray ashes. But here we see her in all her

vigour, changing and renewing and mingling the ruins of her works in

strange association with those of man—the ashes of her volcanoes with

the fragments of temples and baths and the houses of Roman senators

and poets. The whole region lies over a burning mystery, and one has

a[396] constant feeling of insecurity lest the ground should open suddenly

and precipitate one into the very heart of it. Naples itself, strange

to say, a city of more than five hundred thousand inhabitants, is

built in great part within an old broken-down volcanic crater, and the

proximity of its awful neighbour shows that it stands perilously on

the brink of destruction, and may share at any time the fate of

Pompeii and Herculaneum. Were it not for the safety-valves of Vesuvius

and Solfatara, the whole intermediate region, with its towns and

villages and swarming population, would be blown into the air by the

vehement forces that are struggling beneath. It was this elemental

war—fiercer, we have reason to believe, in classic times than

now—that gave rise to the religious fables of the poets. The gloomy

shades of Avernus, the tremendous battles of the gods, the dark

pictures of Tartarus and the Stygian river, were the supernatural

suggestions of a fiery soil. To the fierce throes of volcanic action

we owe the weird mythology of the ancients, which has imparted such a

profound charm to the region, and also, strange as it may seem, the

surpassing loveliness of Nature herself. The fairest regions of the

earth are ever those where the awful power of fire has been at work,

giving to the landscape that passionate expression which lights up a

human face with its most impressive beauty.

The visit of the apostle to Puteoli served many important purposes. He

who had sent his people Israel into Egypt and Babylon that they might

be benefited by coming into contact with other civilisations, sent St.

Paul to this famous region where Greece and Rome—which,

geographically and historically, were turned back to back, the face of

Greece looking eastward, the face of Italy looking westward—seemed to

meet and to blend into each other, in order that his sympathies might

be expanded by coming into contact with all that man could realise of

earthly glory or conceive of religion. We can trace the overruling

Hand that was shaping the destinies of the Church in the course which

he was led to take[397] from Jerusalem to Damascus, and thence to Asia

Minor, Corinth, Athens, Philippi, Puteoli, and Rome; gathering as he

went along the fruits of all the wide diversity of experience and

culture characterising these places, to equip him more thoroughly for

his work for the Gentiles. And we see also how the doctrines of the

Gospel were becoming more clearly and fully unfolded by this method of

progression; how questions were settled and principles carried out

which have shown to us the exceeding riches of Divine grace in a way

that we could not otherwise have known. Like the lines and marks of

the chrysalis which appear on the body of the butterfly when it first

spreads out its wings to fly—like the folds of the bud which may be

seen in the newly-expanded leaf or flower—so Christianity at first

emerged from its Jewish sheath with the distinctive marks of Judaism

upon it. But as it passed westward from the Holy City, it slowly

extricated itself out of the spirit and the trammels of Judaism into

the self-restraining freedom which Christ gives to His people. The

teaching of the Gospel was fully developed, guarded from all possible

misinterpretation, and practically applied to all representative

circumstances of men, through its coming into contact with the events,

persons, and scenes associated with the wonderful missionary

journeyings of the apostle Paul, which began at Jerusalem and

terminated at Rome. When the Gospel reached the Imperial City, its

relations to Jews and Gentiles, bond and free, were fixed for ever,

its own form was perfected, and the conditions for its diffusion

matured; and its history henceforth, like that of Rome itself, was

synonymous with the history of the world.

Printed by R. & R. Clark, Edinburgh.

WORKS BY THE REV. HUGH MACMILLAN, LL.D., F.R.S.E.

BIBLE TEACHINGS IN NATURE. Fifteenth Edition. Crown 8vo, cloth. 6s.

"Ably and eloquently written. It is a thoughtful book, and one that is

prolific of thought."—Pall Mall Gazette.

"Mr. Macmillan writes extremely well, and has produced a book which

may be fitly described as one of the happiest efforts for enlisting

physical science in the direct service of religion. Under his

treatment she becomes the willing handmaid of an instructed and

contemplative devotion."—The Guardian.

"We part from Mr. Macmillan with exceeding gratitude. He has made the

world more beautiful to us, and unsealed our ears to voices of praise

and messages of love that might otherwise have been unheard. We

commend the volume not only as a valuable appendix to works of natural

theology, but as a series of prose idylls of unusual merit."—British

Quarterly Review.

SEQUEL TO "BIBLE TEACHINGS IN NATURE."

THE SABBATH OF THE FIELDS. Fifth Edition. Globe 8vo. 6s.

"This book is a worthy sequel to Mr. Macmillan's admirable 'Bible

Teachings in Nature.' In it there is the same intimate communion with

nature and the same kind of spiritual instruction as in its

predecessor."—Standard.

"This volume, like all Dr. Macmillan's productions, is very delightful

reading, and of a special kind. Imagination, natural science, and

religious instruction are blended together in a very charming

way."—British Quarterly Review.

OUR LORD'S THREE RAISINGS FROM THE DEAD. Globe 8vo. 6s.

"His narrative style is pleasant, and his reflections

sensible."—Westminster Review.

THE MINISTRY OF NATURE. Seventh Edition. Globe 8vo. 6s.

"The author exhibits throughout his writings the happiest

characteristics of a God-fearing, and, withal, essentially liberal and

unprejudiced mind. Of the Essays themselves we cannot speak in terms

of too warm admiration."—Standard.

"We can give unqualified praise to this most charming and suggestive

volume. As studies of nature they are new and striking in information,

beautiful in description, rich in spiritual thought, and especially

helpful and instructive to all religious teachers. If a preacher

desires to see how he can give freshness to his ministry, how he can

clothe old and familiar truths in new forms, and so invest them with

new attractions, how he can secure real beauty and interest without

straining after effect, he could not do better than study this

book."—Nonconformist.

THE TRUE VINE; OR, THE ANALOGIES OF OUR LORD'S ALLEGORY. Fifth

Edition. Globe 8vo. 6s.

"The volume strikes us as being especially well suited for a book of

devotional reading."—Spectator.

"Mr. Macmillan has thrown beautiful light upon many points of natural

symbolism. Readers and preachers who are unscientific will find many

of his illustrations as valuable as they are beautiful."—British

Quarterly Review.

"It abounds in exquisite bits of description, and in striking facts

clearly stated."—Nonconformist.

FIRST FORMS OF VEGETATION. Second Edition. Corrected and Enlarged.

With Coloured Frontispiece and numerous Illustrations. Globe 8vo. 6s.

The first edition of this book was published under the name of

"Footnotes from the Page of Nature; or, First Forms of Vegetation."

Upwards of a hundred pages of new matter have been added to this new

edition, and eleven new illustrations.

"Probably the best popular guide to the practical study of mosses,

lichens, and fungi ever written. Its practical value as a help to the

student and collector cannot be exaggerated, and it will be no less

useful in calling the attention of others to the wonders of nature in

the most modern products of the vegetable world."—Manchester

Examiner.

HOLIDAYS ON HIGH LANDS; OR, RAMBLES AND INCIDENTS IN SEARCH OF ALPINE

PLANTS. Second Edition. Revised and Enlarged. Globe 8vo. 6s.

"A series of delightful lectures on the botany of some of the best

known mountain regions."—Guardian.

"Mr. Macmillan's glowing pictures of Scandinavian nature are enough to

kindle in every tourist the desire to take the same interesting high

lands for the scenes of his own autumn holidays."—Saturday Review.

TWO WORLDS ARE OURS. Third Edition. Globe 8vo. 6s.

"Any one of the chapters may be taken up separately and read with

pleasure and profit by those whose hours for helpful reading are

limited. The ease and grace of style common to all Dr. Macmillan's

writings are palpable in this volume. The miracles of the Old

Testament, as well as the teachings of nature, have interesting

elucidations in it, and readers have the benefit of scriptural studies

and extensive researches in nature and science, made by the author, to

add to their information and sustain their interest."—The

Theological Quarterly.

THE MARRIAGE IN CANA OF GALILEE. Globe 8vo. 6s.

"Dr. Macmillan expounds the circumstances of this miracle with much

care, with a good sense and a sound judgment that are but rarely at

fault, and with some happy illustrations supplied by his knowledge of

natural precept."—The Spectator.

THE OLIVE LEAF. Globe 8vo. 6s.

"Distinguished by felicity of style, delicate insight, and apt

application of the phenomena of nature to spiritual truths that have

rendered the author's previous writings popular. These fresh studies

of forest trees, foliage, and wild flowers are very pleasant

reading."—Saturday Review.

MACMILLAN AND CO., LONDON.