[88]

CHAPTER III

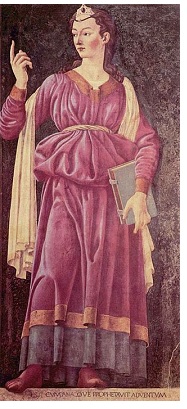

THE CUMĘAN SIBYL

A part of the monotonous coast-line of Palestine extends into the

Mediterranean considerably beyond the rest at Carmel. In this bluff

promontory the Holy Land reaches out, as it were, towards the Western

World; and like a tie-stone that projects from the gable of the first

of a row of houses, indicating that other buildings are to be added,

it shows that the inheritance of Israel was not meant to be always

exclusive, but was destined to comprehend all the countries which its

faith should annex. The remarkable geographical position of this long

projecting ridge by the sea - itself a symbol and prophecy - and its

peculiar physical features, differing from those of the rest of

Palestine, and approximating to a European type of scenery, early

marked it out as a religious spot. It was held sacred from time

immemorial; an altar existed there long before Elijah's discomfiture

of the priests of Baal; the people were accustomed to resort to the

sanctuary of its "high place" during new moons and Sabbaths; and to

its haunted strand came pilgrims from distant regions, to which the

fame of its sanctity had spread. One of the great schools of the

prophets of Israel, superintended by Elisha, was planted on one of its

mountain prominences. The solitary Elijah found a refuge in its bosom,

and came and went from it to the haunts of men like one of its own

sudden storms; and in its rocky dells and dense thickets of oaks and

ever[89]greens were uttered prophecies of a larger history and a grander

salvation, which transcended the narrow circle of Jewish ideas as much

as the excellency of Carmel transcended the other landscapes of

Palestine.

To this instance of striking correspondence between the peculiar

nature of a spot and its peculiar religious history in Asia, a

parallel may be found in Europe. A part of the long uniform western

coast-line of Italy stretches out into the Mediterranean at Cumę, near

the city of Naples. Early colonists from Greece, in search of a new

home, found in its bays, islands, and promontories a touching

resemblance to the intricate coast scenery of their own country. On a

solitary rock overlooking the sea they built their citadel and

established their worship. In this rock was the traditional cave of

the Cumęan Sibyl, where she gave utterance to the inspirations of

pagan prophecy a thousand years before St. John received the visions

of the Apocalypse on the lone heights of the Ęgean isle. The

promontory of Cumę, like that of Carmel, typified the onward course of

history and religion - a great advance in men's ideas upon those of the

past. The western sea-board is the historic side of Italy. All its

great cities and renowned sites are on the western side of the

Apennines; the other side, looking eastward, with the exception of

Venice and Ravenna, containing hardly any place that stands out

prominently in the history of the world. And at Cumę this western

tendency of Italy was most pronounced. On this westmost promontory of

the beautiful land-the farthest point reached by the oldest

civilisation of Egypt and Greece-the Sibyl stood on her watch-tower,

and gazed with prophetic eye upon the distant horizon, seeing beyond

the light of the setting sun and "the baths of all the western stars"

the dawn of a more wonderful future, and dreamt of a—

"Vast brotherhood of hearts and hands,

Choir of a world in perfect tune."

Cumę is only five miles distant from Puteoli, and[90] about thirteen west

of Naples. But it lies so much out of the way that it is difficult to

combine it with the other famous localities in this classic

neighbourhood in one day's excursion, and hence it is very often

omitted. It amply, however, repays a special visit, not so much by

what it reveals as by what it suggests. There are two ways by which it

can be approached, either by the Via Cumana, which gradually ascends

from Puteoli along the ridge of the low volcanic hills on the western

side of Lake Avernus, and passes under the Arco Felice, a huge brick

arch, evidently a fragment of an ancient Roman aqueduct, spanning a

ravine at a great height; or directly from the western shore of Lake

Avernus, by an ancient road paved with blocks of lava, and leading

through an enormous tunnel, called the Grotta de Pietro Pace, about

three-quarters of a mile long, lighted at intervals by shafts from

above, said to have been excavated by Agrippa. Both ways are deeply

interesting; but the latter is perhaps preferable because of the

saving of time and trouble which it effects.

Cumę is only five miles distant from Puteoli, and[90] about thirteen west

of Naples. But it lies so much out of the way that it is difficult to

combine it with the other famous localities in this classic

neighbourhood in one day's excursion, and hence it is very often

omitted. It amply, however, repays a special visit, not so much by

what it reveals as by what it suggests. There are two ways by which it

can be approached, either by the Via Cumana, which gradually ascends

from Puteoli along the ridge of the low volcanic hills on the western

side of Lake Avernus, and passes under the Arco Felice, a huge brick

arch, evidently a fragment of an ancient Roman aqueduct, spanning a

ravine at a great height; or directly from the western shore of Lake

Avernus, by an ancient road paved with blocks of lava, and leading

through an enormous tunnel, called the Grotta de Pietro Pace, about

three-quarters of a mile long, lighted at intervals by shafts from

above, said to have been excavated by Agrippa. Both ways are deeply

interesting; but the latter is perhaps preferable because of the

saving of time and trouble which it effects.

The first glimpse of Cumę, though very impressive to the imagination,

is not equally so to the eye. Crossing some cultivated fields, a bold

eminence of trachytic tufa, covered with scanty grass and tufts of

brushwood, rises between you and the sea, forming part of a range of

low hills, which evidently mark the ancient coast-line. On this

elevated plateau, commanding a most splendid view of the blue, sunlit

Mediterranean as far as Gaeta and the Ponza Islands, stood the almost

mythical city; and crowning its highest point, where a rocky

escarpment, broken down on every side except on the south, by which it

can be ascended, the massive foundations of the walls of the Acropolis

may still be traced throughout their whole extent. Very few relics of

the original Greek colony survive; and these have to be sought chiefly

underneath the remains of Roman-Gothic and medieval dynasties, which

successively occupied the place, and partially obliterated each other,

like the different layers[91] of writing in a palimpsest. Time and the

passions of man have dealt more ruthlessly with this than with almost

any other of the renowned spots of Italy. Some fragments of the

ancient fortifications, a confused and scattered heap of ruins within

the line of the city walls, and a portion of a fluted column, and a

single Doric capital of the grand old style, supposed to belong to the

temple of Apollo, on the summit of the Acropolis, are all that meet

the eye to remind us of this home of ancient faith and prophecy. In

the plain at the foot of the rock is the Necropolis of Cumę, the most

ancient burial-place in Italy, from whose rifled Greek graves a most

valuable collection of archaic vases and personal ornaments were

obtained and transferred to the museums of Naples, Paris, and St.

Petersburg; but the tombs themselves have now been destroyed, and only

a few marble fragments of Roman sepulchral decoration scattered around

indicate the spot. And not far off, partially concealed by earth and

underwood, may be seen the ruins of the amphitheatre, with its

twenty-one tiers of seats leading down to the arena.

You look in vain for any trace of the sanctuary of the most celebrated

of the Sibyls. Her tomb is pointed out as a vague ruin a short

distance from the Necropolis, among the tombs which line the Via

Domitiana; and Justin Martyr and Pausanias both describe a round

cinerary urn found in this spot which was said to have contained her

ashes. The tufa rock of the Acropolis is pierced with numerous dark

caverns and labyrinthine passages, the work of prehistoric

inhabitants, which have only been partially explored on account of the

difficulty and danger, and any one of which might have been the abode

of the prophetess. A larger excavation in the side of the hill facing

the sea, with a flight of steps leading up from it into another

smaller recess, and numerous lateral openings and subterranean

passages, supposed to penetrate into the very heart of the mountain,

and even to communicate with Lake Fusaro, is pointed out by the local[92]

guides as the Sibyl's Cave, which, as Virgil tells us, had a hundred

entrances and issues, from whence as many resounding voices echoed

forth the oracles of the inspired priestess. But we are confused in

our efforts at identification; for another cavern bore this name in

former ages, which was destroyed by the explosion of the combustible

materials with which Narses filled it in undermining the citadel.

This, we have reason to believe, was the cave which Justin Martyr

visited more than seventeen hundred years ago, and of which he has

left behind a most interesting account. "We saw," he says, "when we

were in Cumę, a place where a sanctuary is hollowed in the rock—a

thing really wonderful and worthy of all admiration. Here the Sibyl

delivered her oracles, we were told by those who had received them

from their ancestors, and who kept them even as their patrimony. Also,

in the middle of the sanctuary, they showed us three receptacles cut

in the same rock, and in which, they being filled with water, she

bathed, as they said, and when she resumed her garments, she retired

into the inner part of the sanctuary, likewise cut in the same rock,

and there being seated on a high place in the centre, she prophesied."

But after all you do not care to fasten your attention upon any

particular spot, for you feel that the whole place is overshadowed by

the presence of this mysterious being; and rock, and hill, and bush

are invested with an air of solemn majesty, and with the memory of an

ancient sanctity.

Nature has taken back the ruins of Cumę so completely to her own

bosom, that it is difficult to believe that on this desolate spot once

stood one of the most powerful cities of antiquity, which colonised a

large part of Southern Italy. A sad, lonely, fateful place it is,

haunted for ever by the gods of old, the dreams of men. A silence,

almost painful in its intensity, broods over its deserted fields;

hardly a living thing disturbs the solitude; and the traces of man's

occupancy are few and faint. The air seems heavy with the breath of

the malaria; and[93] no one would care to run the risk of fever by

lingering on the spot to watch the sunset gilding the gloom of the

Acropolis with a halo of kindred radiance. Every breeze that stirs the

tall grasses and the leaves of the brushwood of the dismantled citadel

has a wail in it; the long-drawn murmur of the peaceful sea at the

foot of the hill comes up with a melancholy cadence to the ear; and

even on the beautiful cyclamens and veronicas that strive to enliven

the ruins of the temples of Apollo and Serapis, emblems of the

immortal youth and signs of the renewing power of Nature as they are,

has fallen the gray shadow of the past. Each pathetic bit of ruin has

about it the consciousness of an almost fabulous antiquity, and by its

very vagueness appeals more powerfully to the imagination than any

historical associations. "Time here seems to have folded its wings."

In the immemorial calm that is in the air a thousand years seem as one

day. Through all the dim ages no feature of its rugged face has

changed; and all the potent spell of summer noons can only win from it

a languid smile of faintest verdure. The sight of the scanty walls and

scattered bits of Greek sculpture here take you back to the speechless

ages that have left no other memorials of their activity. What is fact

and what is fable it were difficult to tell in this far-away

borderland where they seem to blend. And I do not envy the man who is

not deeply moved at the thought of the simple, old-world piety that

placed a holy presence in this solitary spot, and of the tender awe

with which the mysterious divinity of Cumę was worshipped by

generations of like passions and sorrows with ourselves—whose very

graves under the shadow of this romantic hill had vanished long ages

before our history had begun.

Every schoolboy is familiar with the picturesque Roman legend of the

Sibyl. It is variously told in connection with the elder and the later

Tarquin, the two Etruscan kings of Rome; and the scene of it is laid

by some in Cumę - where Tarquinius Superbus spent the[94] last years of

his life in exile - and by others in Rome. But the majority of writers

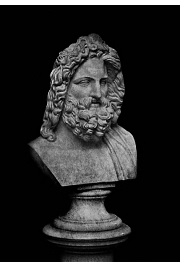

associate it with the building of the great temple of Jupiter on the

Capitoline Hill. Several prodigies, significant of the future fate of

Rome and of the reigning dynasty, occurred when the foundations of

this temple were dug and the walls of it built. A fresh human head,

dripping gore, was found deep down beneath the earth, which implied

that this spot was destined to become the head of the whole world; and

hence the old name of the "Saturnine Hill" was changed to the

"Capitoline." All the gods who had been worshipped from time

immemorial on this hill, when consulted by auguries, gave permission

for the removal of their shrines and altars in order that room might

be provided for the gigantic temple of the great Ruler of the gods,

save Terminus and Youth, who refused to abandon the sacred spot, and

whose obstinacy was therefore regarded as a sign that the boundaries

of the city should never be removed, and that her youth would be

perpetually renewed. But a still more wonderful sign of the future of

Rome was given on this occasion. A mysterious woman, endowed with

preternatural longevity - believed to be no other than Deiphobe, the

Cumęan Sibyl herself, the daughter of Circe and Gnostus, who had been

the guide of Æneas into the world of the dead - appeared before Tarquin

and offered him for a certain price nine books, which contained her

prophecies in mystic rhyme. Tarquin, ignorant of the value of the

books, refused to buy them. The Sibyl departed, and burned three of

them. Coming back immediately, she offered the remaining six at the

same price that she had asked for the nine. Tarquin again refused;

whereupon the Sibyl burned three more volumes, and returning the third

time, made the same demand for the reduced remnant. Struck with the

singularity of the proceeding, the king consulted the augurs; and

learning from them the inestimable preciousness of the books, he

bought them, and the Sibyl forthwith vanished as mysteriously as she[95]

had appeared. This legend reads like a moral apothegm on the increasing value of life as it passes away.

Every schoolboy is familiar with the picturesque Roman legend of the

Sibyl. It is variously told in connection with the elder and the later

Tarquin, the two Etruscan kings of Rome; and the scene of it is laid

by some in Cumę - where Tarquinius Superbus spent the[94] last years of

his life in exile - and by others in Rome. But the majority of writers

associate it with the building of the great temple of Jupiter on the

Capitoline Hill. Several prodigies, significant of the future fate of

Rome and of the reigning dynasty, occurred when the foundations of

this temple were dug and the walls of it built. A fresh human head,

dripping gore, was found deep down beneath the earth, which implied

that this spot was destined to become the head of the whole world; and

hence the old name of the "Saturnine Hill" was changed to the

"Capitoline." All the gods who had been worshipped from time

immemorial on this hill, when consulted by auguries, gave permission

for the removal of their shrines and altars in order that room might

be provided for the gigantic temple of the great Ruler of the gods,

save Terminus and Youth, who refused to abandon the sacred spot, and

whose obstinacy was therefore regarded as a sign that the boundaries

of the city should never be removed, and that her youth would be

perpetually renewed. But a still more wonderful sign of the future of

Rome was given on this occasion. A mysterious woman, endowed with

preternatural longevity - believed to be no other than Deiphobe, the

Cumęan Sibyl herself, the daughter of Circe and Gnostus, who had been

the guide of Æneas into the world of the dead - appeared before Tarquin

and offered him for a certain price nine books, which contained her

prophecies in mystic rhyme. Tarquin, ignorant of the value of the

books, refused to buy them. The Sibyl departed, and burned three of

them. Coming back immediately, she offered the remaining six at the

same price that she had asked for the nine. Tarquin again refused;

whereupon the Sibyl burned three more volumes, and returning the third

time, made the same demand for the reduced remnant. Struck with the

singularity of the proceeding, the king consulted the augurs; and

learning from them the inestimable preciousness of the books, he

bought them, and the Sibyl forthwith vanished as mysteriously as she[95]

had appeared. This legend reads like a moral apothegm on the increasing value of life as it passes away.

Whatever credence we may attach to this account of their origin - or

rather, whatever sediment of historical truth may have been

precipitated in the fable - there can be no doubt that the so-called

Sibylline books of Rome did actually exist, and that for a very long

period they were held in the highest veneration. They were concealed

in a stone chest, buried under the ground, in the temple of Jupiter,

on the Capitol. Two officers of the highest rank were appointed to

guard them, whose punishment, if found unfaithful to their trust, was

to be sewed up alive in a sack and thrown into the sea. The number of

guardians was afterwards increased, at first to ten and then to

fifteen, whose priesthood was for life, and who in consequence were

exempted from the obligation of serving in the army and from other

public offices in the city. Being regarded as the priests of Apollo,

they had each in front of his house a brazen tripod, similar to that

on which the priestess of Delphi sat.

The contents of the Sibylline books, being supposed to contain the

fate of the Roman Empire, were kept a profound secret, and only on

occasions of public danger or calamity, and by special order of the

senate, were they allowed to be consulted. When the Capitol was burned

in the Marsic war, eighty-two years before Christ, they perished in

the flames: but so seriously was the loss regarded that ambassadors

were sent to Greece, Asia Minor, and Cumę, wherever Sibylline

inspiration was supposed to exist, to collect the prophetic oracles,

and thus make up as far as possible for what had been lost. In Cumę

nothing was discovered; but at Erythręa and Samos a large number of

mystic verses, said to have been composed by the Sibyl, were found.

Some of them were collected into a volume, after having been purged

from all spurious or suspected elements; and the volume was brought to

Rome, and deposited in two gilt cases at[96] the base of the statue of

Apollo, in the temple of that god on the Palatine.

More than two thousand prophetic books, pretending to be Sibylline

oracles, were found by Augustus in the possession of private persons;

and these were condemned to be burned, and in future no private person

was allowed to keep any writings of the kind. But in spite of every

attempt to authenticate the books that were publicly accepted, the new

collection was never regarded with the same veneration as the original

volumes of Tarquin which it replaced. A certain suspicion of

spuriousness continued to cling to it, and greatly diminished its

authority. It was seldom consulted. The Roman emperors after

Tiberius - who still further sifted it - utterly neglected the

received collection; and not till shortly before the fatal battle of

the Milvian Bridge, which overthrew paganism, was it again brought

out, by Maxentius, for the purpose of indicating the fate of the

enterprise. Julian the Apostate, in his attempt to galvanise the dead

pagan religion into the semblance of life, sought to revive an

interest in the Sibylline oracles, which were so closely identified

with the political and religious fortunes of Rome. But his effort was

vain: they fell into greater oblivion than before; and at last they

were publicly burned by Stilicho, the father-in-law of the Emperor

Honorius—called the Defender of Italy—whose own execution as a

traitor at Ravenna shortly afterwards was considered by the pagan zealots as the just vengeance of the gods on his dreadful sacrilege.

Unlike the Jewish and Indian faiths, the Greek and Roman religions had

no authoritative writings, and were not embodied in a system of

elaborate dogmas. The Sibylline oracles may therefore be said to have

formed their sacred scriptures, and to have served the purpose of a

common religious creed in securing national unity. The original books

of the Cumęan Sibyl were written in Greek, which was the language of

the whole of the south of Italy at that time. The oracles were

inscribed upon[97] palm leaves; to which circumstance Virgil alludes in

his description of the sayings of the Cumęan Sibyl being written upon

the leaves of the forest. They were in the form of acrostic verses;

the letters of the first verse of each oracle containing in regular

sequence the initial letters of all the subsequent verses. They were

full of enigmas and mysterious analogies, founded upon the numerical

value of the initial letters of certain names. It is supposed that

they contained not so much predictions of future events, as directions

regarding the means by which the wrath of the gods, as revealed by

prodigies and calamities, might be appeased. They seemed to have been

consulted in the same way as Eastern nations consult the Koran and

Hafiz. There was no attempt made to find a passage suitable to the

occasion, but one of the palm leaves after being shuffled was selected

at random. To this custom of drawing fateful leaves from the Sibylline

books-called in consequence sortes sibyllinæ—there is frequent

allusion by classic authors. We know that the writings of Homer and

Virgil were thus treated. The elevation of Septimius Severus to the

throne of the Roman Empire was supposed to have been foretold by the

circumstance that he opened by chance the writings of Lampridius at

the verse, "Remember, Roman, with imperial sway to rule the people."

The Bible itself was used by the early Christians for such purposes of

divination. St. Augustine, though he condemned the practice as an

abuse of the Divine Word, yet preferred that men should have recourse

to the Gospels rather than to heathen works. Heraclius is reported by

Cedrenus to have asked counsel of the New Testament, and to have been

thereby persuaded to winter in Albania. Nicephorus Gregoras frequently

opened his Psalter at random in order that there he might find support

in the trial under which he laboured. And even in these enlightened

days, it is by no means rare to find superstitious men and women using

the sacred Scriptures as the old Greeks and Romans used the Sibylline[98]

oracles—dipping into them by chance for indications of the Divine

Will.

The Cumęan Sibyl was not the only prophetess of the kind. There were

no less than ten females, endowed with the gift of prevision, and held

in high repute, to whom the name of Sibyl was given. We read of the

Persian Sibyl, the Libyan, the Delphic, the Erythræan, the

Hellespontine, the Phrygian, and the Tiburtine. With the name of the

last-mentioned Sibyl tourists make acquaintance at Tivoli. Two ancient

temples in tolerable preservation are still standing on the very edge

of the deep rocky ravine through which the Anio pours its foaming

flood. The one is a small circular building, with ten pillars

surrounding the broken-down cella, whose familiar appearance is often

represented in plaster models and bronze and marble ornamental

articles, taken home as souvenirs by travellers; and the other stands

close by, and has been transformed into the present church of St.

Giorgio. This latter temple is supposed, from a bas-relief found in

it, representing the Sibyl sitting in the act of delivering an oracle,

to be the ancient shrine of the Sibyl Albunea mentioned by Horace,

Tibullus, and Lactantius. The earliest bronze statues at Rome were

those of the three Sibyls, placed near the Rostra, in the middle of

the Forum. No specimens of the literature of Rome precede the

Sibylline books, except the rude hymn known as the Litany of the Arval

Brothers, dating from the time of Romulus himself, which is simply an

address to Mars, the Lares, and the Semones, praying for fair weather

and for protection to the flocks. And it is thus most interesting to

notice that the two compositions which lay at the foundation of all

the splendid Latin literature of later ages were of an eminently

religious character.

One of the most remarkable things connected with the pagan Sibyls were

the apocryphal Jewish and Christian prophecies to which they gave

rise. When the sacred oak of Dodona perished down to the ground, out

of its roots sprang up a fresh growth of fictitious prophetic[99]

literature. This literature emanated from different nationalities and

different schools of thought. It combined classical story and

Scripture tradition. Most of it was the product of pre-Christian

Judaism, and seemed to have been composed in times of great national

excitement. The misery of the present, the prospect still more gloomy

beyond, impelled its authors to anxious inquiries into the future. The

books were written, like the genuine Sibylline books, in the metrical

form, which the old Greek tradition had consecrated to religious use;

and their style so closely resembled that of the Apocalypse and the

Old Testament prophecies, that some pagan writers who accepted them as

genuine did not hesitate to say that the writers of the Bible had

plagiarised parts of their prophecies from the oracles of the Sibyls.

Few fragments of the genuine Sibylline books remain to us, and these

are to be found chiefly in the writings of Ovid and Virgil, whose

"Golden Age" and well-known "Fourth Eclogue" were greatly indebted for

their materials to them. But we possess a large collection of the

Judæo-Christian oracles, which were probably gathered together by some

unknown editor in the seventh century. Originally there were fourteen

books of unequal antiquity and value, but some of them have been lost.

Cardinal Angelo Mai discovered in the Ambrosian Library at Milan a

manuscript which contained the eleventh book entire, besides a portion

of the sixth and eighth books; and a few years later, among the secret

stores of the Vatican Library, he found two other manuscripts which

contained entire the last four books of the collection. These were

published in Rome in 1828. The best edition of all the extant books is

that which M. Alexandre issued in Paris, under the name of Oracula

Sibyllina. This editor exaggerates the extent of the Christian

element in the Sibylline prophecies; but his dissertation on the

origin and value of the several portions of the books is exceedingly

interesting. The oldest book is undoubtedly the third, part of which

is preserved in the writings of[100] Theophilus of Antioch, and originally

consisted of one thousand verses, most of which we possess. It was

probably composed at the beginning of the Maccabean period, about 146

B.C., when Ptolemy VII. (Physcon) had become king of Egypt, and the

bitter enemy of the Jews in Alexandria, and when the Jewish nation in

Palestine had been rejoicing in their independence, through the

overthrow of the empire of the Seleucidæ by the usurper Tryphon. The

fourth book was written soon after the eruption of Vesuvius in the

year of our era 79, and is a most interesting record of Jewish

Essenism. It contains the first anticipation of the return of Nero,

but in a Jewish form, without Nero's death and resuscitation. The last

of the Sibylline books seems to have been written about the beginning

of the seventh century, and was directed against the new creed of

Islam, which had suddenly sprung up, and in its fierce fanaticism was

carrying everything before it. In this apocalyptic literature—the

last growth of Judaism—the voice of paganism itself was employed to

witness for the supremacy of the Jewish religion. It embraces all

history in one great theocratic view, and completes the picture of the

Jewish triumph by the prophecy of a great Deliverer, who shall

establish the Jewish law as the rule of the whole earth, and shall

destroy with a fiery flood all that is corrupt and perishable. In

these respects the Jewish Sibylline oracles have an interesting

connection with other apocryphal Jewish writings, such as the Fourth

Book of Esdras, the Apocalypse of Henoch, and the Book of Jubilees;

and they may all be regarded as attempts to carry down the spirit of

prophecy beyond the canonical Scriptures, and to furnish a supplement

to them.

So highly prized was this group of apocryphal Jewish oracles by the

primitive Christians, that several new ones were added to them by

Christian hands which have not come down to us in their original

state. They were regarded as genuine productions, possessing an

independent authority which, if not divine, was certainly[101]

supernatural; and some did not hesitate even to place them by the side

of the Old Testament prophecies. In the very earliest controversies

between Christians and the advocates of paganism, they were appealed

to frequently as authorities which both recognised. Christian

apologists of the second century, such as Tatian, Athenagoras, and

very specially Justin Martyr, implicitly relied upon them as

indisputable. Even the oracles of the pagan Sibyl were regarded by

Christian writers with an awe and reverence little short of that which

they inspired in the minds of the heathen themselves. Clement of

Alexandria does not scruple to call the Cumęan Sibyl a true

prophetess, and her oracles saving canticles. And St. Augustine

includes her among the number of those who belong to the "City of

God." And this idea of the Sibyl's sacredness continued to a late age

in the Christian Church. She had a place in the prophetic order beside

the patriarchs and prophets of old, and joined in the great procession

of the witnesses for the faith from Seth and Enoch down to the last

Christian saint and martyr. In one of the grandest hymns of the Roman

Catholic Church, composed by Tommaso di Celano at the beginning of the

fourteenth century, there is an allusion to her, taken from the

well-known acrostic in the last judgment scene in the eighth book of

the Oracula Sibyllina—

"Dies iræ, dies illa,

Solvet sæclum in favilla,

Teste David cum Sibylla."

The strange Italian mystic of the fifteenth century, Pico della

Mirandola, who sought to reconcile the Christian sentiment with the

imagery and legends of pagan religion, rehabilitated the Sibyl, and

consecrated her as the servant of the Lord Jesus. And he was but a

specimen of the many humanists of that age who believed that no

oracle that had once spoken to living men and women could ever wholly

lose its vitality. Like the Delphic Pythia, old, but clothed as a

maiden, the ancient Sibyl appeared[102] to them in the garments of

immortal youth, with the charm of her early prime.

The dim old church of Ara Coeli in Rome, which occupies the site of

the celebrated temple of Jupiter on the Capitol, and in which Gibbon

conceived the idea of his great work on the Decline and Fall of the

Roman Empire, is said to have derived its name from an altar bearing

the inscription, "Ara Primogeniti Dei," erected in this place by

Augustus, to commemorate the Sibylline prophecy of the coming of our

Saviour. She was a favourite subject of Christian art in the middle

ages, and was introduced by almost every celebrated painter, along

with the prophets and apostles, into the cyclical decorations of the

Church. Every visitor to Rome knows the fine picture of the Sibyls by

Pinturicchio, on the tribune behind the high altar of the Church of

St. Onofrio, where Tasso was buried; and also the still grander head

of the Cumęan Sibyl, with its flowing turban by Domenichino, in the

great picture gallery of the Borghese Palace. But the highest honour

ever conferred upon the Sibyls was that which Michael Angelo bestowed

when he painted them on the spandrils of the wonderful roof of the

Sistine Chapel. These mysterious beings formed most congenial subjects

for the mystic pencil of the great Florentine, and therefore they are

more characteristic of his genius than almost any other of his works.

He has painted them along with the greater prophets, Isaiah, Jeremiah,

Ezekiel, Daniel, Jonah, in throne-like niches surrounding the

different incidents of the creation. They look like presiding deities,

remote from all human weaknesses, and wearing on their faces an air of

profound mystery. They are invested, not with the calm, superficial,

unconscious beauty of pagan art, but with the solemn earnestness and

travail of soul characteristic of the Christian creed, wrinkled and

saddened with thought and worn out with vigils; and are striking

examples of the truth, that while each human being can bear his own

burden, the burden of the world's mystery and[103] pain crushes us to the

earth. The Persian Sibyl, the oldest of the weird sisterhood, to whom

the sunset of life had given mystical lore, holds a book close to her

eyes, as if from dimness of vision; the Libyan Sibyl lifts a massive

volume above her head on to her knees; the Cumęan Sibyl intently reads

her book at a distance from her dilated eyes; the Erythræan Sibyl,

bareheaded, is about to turn over the page of her book; while the

Delphic Sibyl, like Cassandra the youngest and most human-looking of

them all, holds a scroll in her hand, and gazes with a dreamy

mournfulness into the far futurity. These splendid creations would

abundantly reward the minute study of many days. They show how

thoroughly the great painter had entered into the history and spirit

of these mysterious prophetesses, who, while they bore the sins and

sorrows of a corrupt world, had power to look for consolation into the

secrets of the future.

Very beautiful was this reverence paid to the Sibyl amid all the

idolatries of paganism and the corruptions of later Judaism. We may

regard it as a relic of the early piety of the world. One who could

pass over the interests and distractions of her own time, and fix her

gaze upon the distant future, must have seemed far removed from the

common order of mankind, who live exclusively in the present, and can

imagine no other or higher state of things than they see around them.

Standing as the heirs of all the ages on this elevated vantage-ground

and looking back upon the long course of the centuries—upon the

eventful future of the Sibyl, which is the past to us—it seems a

matter of course that the world should have spun down the ringing

grooves of change as it has done; and we fancy that this must have

been obvious to the world's gray fathers. But though the age of the

Sibyl seemed the very threshold of time, there was nothing to indicate

this to her, nothing to show that she lived in the youth of the world,

and that it was destined to ripen and expand with the process of the

suns. The same horizon that bounds us in these last days, bound[104] her

view in these early days; and things seemed as fully developed and

stereotyped then as now, and to-morrow promised to be only a

repetition of to-day. To realise, therefore, that the world had a

future, and to take the trouble of thinking what would happen a

thousand years off, indicated no common habit of mind.

And we are the more impressed by it when we consider the spots

bewitched by the spell of Circe where it was exercised. That persons

dwelling in lonely, northern isles, where the long wash of the waves

upon the shore, and the wild wail of the wind in mountain corries

stimulated the imagination, and seemed like voices from another world,

should see visions and dream dreams, does not surprise us. The power

of second sight may seem natural to spots where nature is mysterious

and solemn, and full of change and sudden transitions from storm to

calm and from sunshine to gloom. But at Cumę there is a perpetual

peace, an unchanging monotony. The same cloudless sky overarches the

earth day after day, and dyes to celestial blue the same placid sea

that sleeps beside its shore. The fields are drowsy at noon with the

same stagnant sunshine; and the same purple glory lies at sunset on

the entranced hills; and the olive and the myrtle bloom through the

even months with no fading or brightening tint on leaf or stem; and

each day is the twin of that which has gone before. Nature in such a

region is transparent. No mist, or cloud, or shadow hides her secrets.

There is no subtle joy of despair and hope, of decay and growth,

connected with the passing of the seasons. In this Arcadian clime we

should expect Nature to lull the soul into the sleep of contentment on

her lap; and in its perpetual summer happy shepherds might sing

eclogues for ever, and, satisfied with the present, have no hope or

wish for the future. How wonderful, then, that in such a charmed

lotus-land we should meet with the mysterious unrest of soul, and the

fixed onward look of the Sibyl to times widely different from her

own.

[105]

And not only is this forward-looking gaze of the Sibyl contrary to

what we should have expected in such a changeless land of beauty and

ease; it is also contrary to what we should have expected from the

paganism of the people. It is characteristic of the Greek religion, as

indeed of all heathen religions, that its golden age should be in the

past. It instinctively clings to the memory of a former happier time,

and shrinks from the unknown future. Its piety ever looks backward,

and aspires to present safety or enjoyment by a faithful imitation of

an imaginary past. It is always "returning on the old well-worn path

to the paradise of its childhood," and contrasting the gloom that

overhangs the present with the radiance that shone on the morning

lands. In every crisis of terror or disaster it turns with unutterable

yearnings to the tradition of the happy age. Or, if it does look

forward to the future, it always pictures "the restoration of the old

Saturnian reign"; it has no standard of future excellence or future

blessedness to attain to, and no yearnings for consummation and

perfection hereafter. The very name given to the south of Italy was

Hesperia, the "Land of the Evening Star," as if in token of its

exhausted history; and it was regarded as the scene of the fabled

golden age from which Saturn and the ancient deities had been expelled

by Jupiter. But contrary to this pagan instinct, the Cumęan Sibyl

stretched forward to a distant heaven of her aspirations and hopes—to

a nobler future of the world, not sentimental and idyllic, but epic

and heroic. She pictured the blessing or restoration of this earth

itself as distinct from an invisible world of happiness. And in this

respect she is more in sympathy with the Jewish and Christian

religions than with her own. The golden age of the Hebrews was in the

future, and was connected with the coming of the Messiah, who should

restore the kingdom again unto Israel. And the characteristic of the

Christian religion is hope, the expectation of the times of the

restitution of all things, and the realisation of the "one far-off

divine event to which the whole[106] creation moves." It is this hopeful

element pervading them that gives to the lively oracles of Holy

Scripture the triumphant tone which distinguishes them so markedly

from the desponding spirit of all false religions, ancient and modern.

The subject of the Sibyl brings us to the vexed question of the

connection between pagan and Hebrew prophecy. How are we to regard the

vaticinations of the heathen oracle? That the great mass of the

Sibylline books is spurious is glaringly obvious. But there is a

primitive residuum which seems to remind us that the spirit of early

prophecy still retained its hold over human nature amid all the

corruptions of heathendom, and secured for the Sibyl a sacred rank and

authority. We have seen with what reverence the greatest fathers of

the Christian Church regarded her. While there was undoubtedly much

delusion and deception, conscious or unconscious, mixed up with it, we

are constrained at the same time to acknowledge that there was some

reality in this prophetic element of paganism, which cannot be

explained away as the result of mere political or intellectual

foresight or accidental coincidence. It was not all imposture. As a

ray of light is contained in all that shines, so a ray of God's truth

was reflected in what was best in this pagan prophecy. The fulfilment

of many of the ancient oracles cannot be denied without a perversion

of all history. There was no doubt an immense difference between the

Hebrew prophets and the pagan Sibyl. The predictions of the Sibyl were

accompanied by strange fantastic circumstances, and wore the

appearance of a blind caprice or arbitrary fate; whereas the

announcements of the Hebrew prophets, founded upon the denunciation of

moral evil and the reign of sacred and peremptory principles of

righteousness in the world, were calm, dignified, and self-consistent.

But we cannot, notwithstanding, deny to pagan prophecy some share in

the higher influence which inspired and moulded Hebrew prophecy. The

apostle of the Gentiles took this view when he called[107] Epimenides the

Cretan a prophet. The Bible recognises the existence of true prophets

outside the pale of the Jewish Church. Balaam, the son of Beor, was a

heathen living in the mountains beyond the Euphrates; and yet the form

as well as the substance of his prophecy was cast into the same mould

as that of the Hebrew prophets. He is called in the Book of Numbers

"the man whose eyes are open;" and God used this power as His organ of

intercourse with and influence upon the world. The grand record of his

vision is the first example of prophetic utterance respecting the

destinies of the world at large; and we see how the base and

grovelling nature of the man was overpowered by the irresistible force

of the prophetic impulse within him, so that he was constrained to

bless the enemies he was hired to curse. And in this respect he

represents the purest of the ancient heathen oracles; and his answer

to Balak breathes the very essence of prophetic inspiration, and is

far in advance of the spirit and thought of the time, reminding us of

the noble rebuke of the Cumęan Sibyl to Aristodicus, and of the oracle

of Delphi to Glaucus.

God did not leave the Gentile nations without some glimpses of the

truth which He had revealed so fully and brightly to His own chosen

people. While He was the glory of His people Israel, we must not

forget that He was a light to lighten the Gentiles. He gave to them

oracles and sibyls, who had the "open eye," and saw the vision of the

years, and witnessed to a light shining in the darkness, and brought

God nearer to a faithless world. Beneath the gross external polytheism

of the multitude there were deep, primitive springs of godliness, pure

and undefiled, working out their manifestation in noble lives; and

those who have ears to hear can listen to the sound of these ancient

streams as they flow into the river of life that makes glad the city

of our God. We gain immensely by considering the prophetical spirit of

Israel as a typical endowment, and the training of the Jews in the

household of God, and under His own im[108]mediate eye, as the key to the

right apprehension of the training of Greece and Rome. The unconscious

prophecies of heathendom pointed in their own way, as well as the

articulate divine prophecies of Israel, to the coming of Him who is

the Desire of all nations, and the true Light that lighteth every man

that cometh into the world. The wise men of Greece saw the sign of the

Son of Man in some such way as the Magi saw the star in the East. They

were, according to Hegel's beautiful comparison, "Memnons waiting for

the day." And not without deep significance did the female soothsayer

from the oracle of Dionysius, the prophet-god of the Macedonians, whom

Paul and Silas met when they first landed on European soil, greet them

with the words, "These men are the servants of the most high God,

which show unto us the way of salvation." In that wonderful confession

we recognise the last utterance of the oracle of Delphi and the Sibyl

of Cumę, as they were cast out by a higher and truer faith. Their

mission was accomplished and their shrine deserted when God's way was

known upon the earth, and His saving health among all nations.

"And now another Canaan yields

To thine all-conquering ark;

Fly from the 'old poetic fields,'

Ye Paynim shadows dark!

Immortal Greece, dear land of glorious lays,

Lo! here the unknown God of thine unconscious praise.

"The olive wreath, the ivied wand,

'The sword in myrtles drest,'

Each legend of the shadowy strand

Now wakes a vision blest;

As little children lisp, and tell of heaven,

So thoughts beyond their thoughts to those high bards were given."

Contents | Previous Chapter | Next Chapter